Life & Limb - A monthly podcast about Living Well with Limb Loss

Cycling for Ukrainian Amputees

Episode Date: May 29, 2024

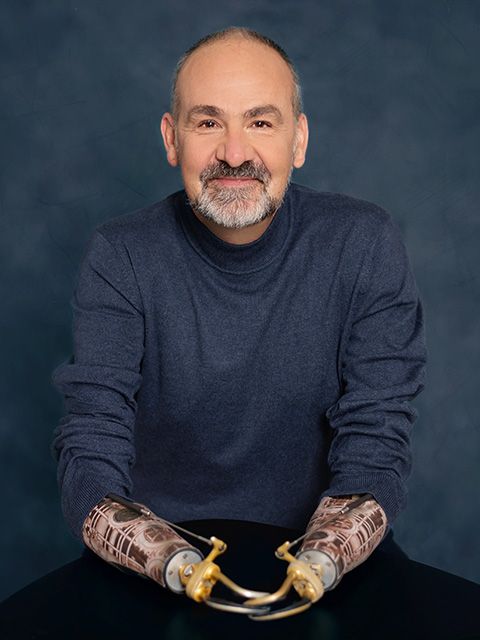

Jeff Tiessen: Welcome to Life in Limb, a podcast from Thrive magazine all about living well with limb loss and limb difference. I'm Jeff Tiessen, publisher of Thrive magazine and your podcast host. My guest this episode is someone who I haven't met until a few minutes ago, but I got an email from him just recently and I was really taken and fascinated by it. And I thought right away that thrive magazine readers need to know more about Jakob and how great it would be for our podcast listeners to hear his remarkable story, too. So, we have Jakob Kepka with us today. He's from London, Ontario, an above knee amputee, a serious cyclist, and that's an understatement for sure. And you'll understand why. And for me to share more about his vision and his life would not do it justice. So, we're going to let Jakob do that for us. So, Jakob, welcome. How are you?

Jakob Kepka: Fine, thank you. Thanks for having me today.

Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, it's a pleasure. So, I said you're from London, but originally you're from?

Jakob Kepka: I'm from Eastern Ontario.

Jeff Tiessen: Right. Small town.

Jakob Kepka: A small town south of Ottawa, raised on a farm and yeah, you know, my parents were first generation Canadians, post second world war refugees. My father was a Polish military man from the Second World War. Mother was a war bride of German background and they immigrated here in the late forties and made Canada their home. And my sister and I were raised on the farm. My sister was born overseas just before they immigrated here. I was born here and I was raised in a very, let's say, European lifestyle. You know, like, my father, being a Polish patriot as he was, was very angry at the state of the world, in eastern Europe especially, that Poland didn't have a chance for democracy. And in the household we spoke Polish.

And he instilled in me, his son, a great love for Poland. Even though I never had been there. I didn't go back. I never went to Poland till 2016, because as a young man, my father kept me from going because I was classed as a polish citizen and I would have been taken into the communist army, probably. So, yeah, short story, that's how my upbringing led me to what I’ve doing the last few years.

Jeff Tiessen: That's really some good context and background for what we're going to talk about today. It really is relevant. And when you talk about your dad's military background, you have that as well. And before we get into that interesting story and very remarkable volunteer background, I'm going to ask you this. You know why. You know the answer very distinctly, I'm sure, and why it's important to you. But how far is it from Krakow, Poland, to Kyiv, Ukraine?

Jakob Kepka: According to the route we're picking, it's about 900 km.

Jeff Tiessen: All right, so for our listeners, what's with that route that you picked? Let's talk about the ride.

Jakob Kepka: Well, this was my personal idea when I came back from Ukraine. Two years this coming November. So this idea sprouted in my head that to inspire the growing number of Ukrainian amputees, it'd be great to raise funds. I know they're short on prosthetics and prosthetic technicians, so I said, wow, a ride would be great. I'm a cyclist. Show them that anything's possible.

It's not your body that restricts you, it's your mental attitude. And if I can do it, at my age, anybody can do it. And so because of my contacts from working over there two years ago, all my Polish friends are centered living around the Krakow area. So I said, what about I cycle from Krakow, to Kyiv, the capital, because you can tell Ukrainian amputees, oh, there's this crazy Canadian para-cyclist, he's going to cycle and fundraise for you, 1000 km rounded off. But it wouldn't have the effect unless I did it there.

They'd hear about it and they'd go, well, it's another, you know, somebody raising money for us for the Ukrainian war effort and big deal. But if they see me do it, if they see me cross the border and willing to take to risks that a war entails and Ukrainian drivers entail, which I'm more afraid of than anything Russian, that would inspire them by riding through towns and villages, because there's not a town, village, homestead in that country that's not been affected by the war.

Jeff Tiessen: So you said at your age, so let's share that. How old are you?

Jakob Kepka: I'll be 67 in the fall. 900 kilometres, If I was training here in Canada with good road conditions and relative safety, that'd be like nine days for me; nine days of riding.

Jeff Tiessen: But it won't be that there.

Jakob Kepka: It won't be that there. I'm leaving on May 31 from Canada to go to Poland, where my first job over there is to get in the car with a friend of mine that's assisting with the ride, a Polish friend. And we're driving the road because no one could tell me what the road to Lviv is like, because I worked in that area two years ago, and it's a good highway, but I don't know what I'll be dealing with as I head farther east, right? And I want to see the roads. I want to not just see the road condition, but the width and that we might have to modify to the route to accommodate the fact that, you know, I'm a one-legged cyclist. The way I ride is I don't wear a prosthetic. I pedal with one leg, and I have a cycling pod, like a socket attached to my seat post, which I slip my stump into, and I pedal with one leg. So, you know, you'd like to have some shoulder, a bit of a leeway in regards to the pavement. The gentleman that's coming along is my driver in a camper we've been offered.

He's driven a lot of the roads between Lviv and Kyiv because he's been there over two summers during the war, and he says the roads are still in pretty good condition between Lviv and Kyiv. So hopefully, once I see it, there won't be too many detours that we make to head on the good road. Though I do expect to be making detours. If I find out that there's an orphanage, a medical facility, where amputees are being rehabilitated or in treatment, I'll make a detour and go see them on my bike.

Jeff Tiessen: You referred earlier to Ukrainian drivers, and how that could be quite dangerous. For us, we're not thinking about Ukrainian drivers in Ukraine right now, and I'd certainly be remiss as a journalist if I didn't ask you what about the war that's going on? What kind of danger would you perceive yourself taking here, in that regard?

Jakob Kepka: I just heard today that Kharkiv was hit again. Um, Lviv is relatively a safe city. When I was there two years ago, we would take weekends where we could sleep on a real bed and have a shower. And a real shower, instead of living the way we were living in warehouses or schools. When we were there, you'd hear the sirens. And in the village I was working in in Ukraine, there was nowhere to go, so you just kept working. We were doing renovations to an old building to make a new medical center for this town. When I was there before, regarding the Russians, I'm a fatalist. If it's my time to go, it's my time to go. Whether I'm in Ukraine or here, if it's doing something worthwhile, then so it is. I'm not going to worry about it, and I'll let my maker deal with the consequences if it was really worthwhile. I'm not afraid of the war itself.

I'm afraid of, like I said, Ukrainian drivers, because I'll be dealing with them more consistently, because it's pretty hairy on the roads there. The rules of the road have sort of disappeared. They're supplying the troops, getting humanitarian aid in, and people are still going on with their everyday lives. Right. And the paradox in vehicles there is phenomenal. You'll see a $100,000 Mercedes flying down the road, followed by a 60-year-old Lada that can barely go 40 km an hour, and then a family going to church, pulled by a horse and cart. And I'll have to maneuver all that. So that's why I'm happy. I will have a vehicle, a camper, and my driver, Stephen, who I met over there two years ago. He's from the UK.

He'll be behind me, you know, with four ways on, and I'll be tucked in, hopefully in front of him. When I'm over there, because I have so much preparation time, almost three months before the actual ride, we'll be getting in contact with the authorities in Ukraine and giving them a heads up. And the cycling groups, we're going to put the word out to any cycling clubs to come along and keep me company between towns and let me draft off them a bit.

Jeff Tiessen: To fill in the blanks a little bit. You referred to humanitarian aid, but you were there on a humanitarian mission recently, and you had referred to refurbishing old buildings into a medical facility. And then, if I understand right, some R and R, rest and relaxation time, took you to Lviv, and that's where the real impact of seeing other amputees, as you've described, without prosthetic devices, but on crutches or even not, had a real impact on you, did it not? Do I understand that right?

Jakob Kepka: Yeah. Like, I went over there as a volunteer with an American organization that only took veterans, and they were in dire need of anyone that spoke either Russian, Polish or Ukrainian. I speak Polish, so I applied. I did not expect to be called up and asked because you know, you admit that you're an above knee amputee, and, you know, the chances of them taking on somebody to a war zone I thought were minimal. But within two weeks, I got a call from a retired US Air Force flight sergeant, and after the interview online, she asked me when could I leave.

So I left almost within the month and ended up eventually translating for their office on the border, then working with a Polish group transporting humanitarian aid into Lviv and also on the border. At that time, the border was overcrowded. People were still lined up. Look, I remember one day we were checking tractor trailers that would take a week to cross the border. They were parked along the highway.

Because there were several of us vets who had construction experience, we were asked to renovate old offices in a village called Nahatcheev in the Lviv Oblast, and convert them into a medical center. And we started that project on July 4, two years ago, and I left October 31. I was the last one to leave. And we lived in pretty rough conditions, in a very poor little village of 3500 people with no infrastructure. So at first we lived on worn out old cots in the school over the summer, and they made our shower in the old scullery, which worked great for the able-bodied guys. But me hopping around, pushing an old metal chair to get under the water and out safely was not the safest way to take a shower. But on the weekends, we either went back to Poland to do our laundry or we went to Lviv, which was about 100 km down the highway. And Lviv was like a liberty town for the Ukrainian military. By liberty, I mean leave. You know, a week, or 48 hour-passes, family leaves, and you'd see a lot of military personnel there. The whole area is full of army bases now, but also several hospitals that had been converted to military hospitals.

And, you know, it was quiet. Lviv is a beautiful city, very inexpensive to entertain yourself; hotel rooms were the equivalent of like $75 Canadian a night, and you wouldn't get a hotel room like that for $700 a night here. And I was walking around the old town, the old city, with my colleagues and even my son, who came to work with us. He's a carpenter in France. And I'd be seeing these new amputees still with bandages on, maybe on a day pass out of the hospital. They were all with crutches. There was upper extremity and lower extremity amputees, and here I'm walking around with my microprocessor knee and walking pretty well, and they're staring at me. And I remember one young man in particular. I think he was with his parents, and he was an AK, and he was on crutches. And we were in the main square of Lviv. It's all surrounded with restaurants and buskers and singing and all very patriotic, you know, the Ukrainian flag everywhere. Humanitarian aid workers milling around, all the languages, you know, English with every accent. And this young man stopped dead, and stared at me as I'm walking, and I did not have the courage to stop and talk to him. One, my Ukrainian isn't the best, but I could see something in his eyes, he had been going with his folks, his father on one side, his mother on the other. I assume that's who they were. They were much older, and his head was down, you know, like a dejected look. He wasn't paying attention to all the activity in the square. But when he saw me, he picked up, you know, looked up right away and stared at me. I regret not stopping to talk to him. I could have found somebody bilingual there, and just, you know, give them hope. And it bothered me

And then I went to the hospital there once. I had problems with my socket, and they had to fix my socket, and I ended up in the army hospital, and I saw that the facilities they had. They were working out of a container, a room the size of maybe ten by ten. The container was for the molding, doing the actual test sockets, making sockets, but that was it. They didn't have the facilities. And then I read articles that when the war started, they only had 200 prosthetists and technicians in the whole country, and several months ago, they were looking at over 20-some thousand new amputees. A lot of them are bilaterals.

And so when I came home, the guilt for not talking to that young man ate at me, and I came up with this idea to show them that nothing's impossible. I'm a cyclist. It took me three years to learn to ride one legged, but I did it, and all it takes is the willingness to do it. And me doing a ride here and putting it on YouTube or whatever and getting it over to them. The majority of them would never see it. They would never know about it, that this guy is riding for Ukrainians, fundraising to get them prosthetics. I'm linked up with a Canadian prosthetic NGO and an American one that do work over in Ukraine. But if they see me do it in their country, then that'll make an impact.

Jeff Tiessen: Yeah. That's authentic, right? And that's not arm's length volunteer work, let alone putting yourself at risk and at danger. And no doubt, Jakob, I mean, that one person, I can see and hear in your voice, it's still upsetting to you, but think how many more you're going to impact.

Jakob Kepka: Yeah, I hope so. Like, when I thought of this, I was alone, and my Polish friend, my close friend, and he is on the board of a Polish NGO for the Ukrainians, said, yeah, I'll talk to everybody that you know over here about the ride. And they came back and said it was a good idea. But I didn't realize setting up a ride in a foreign country, in a war zone, would be so complicated. I thought I would just get over there, jump on the bike, and go for a ride.

Jeff Tiessen: Did you?

Jakob Kepka: It's not that way. So first I reached out to an organization I met over there, a prosthetic NGO, an American one, the Polish group I was affiliated with on the Polish Ukrainian border. That summer, they brought me back from the job in Ukraine. We got somebody we want you to meet. We want you to meet tonight. And it was a person from the United States, a Polish American woman with an organization that repurposes used prosthetics. They tear them down, clean them up, and repurpose. And they were using the Polish organization I was with attached to ship it to Odessa. They had a bunch of prosthetics that were parts to go to Odessa.

So I met this young woman. We talked, and she was just fascinated that there's a guy that's an amputee that's doing construction work and warehouse work over here, and he's an amputee. And when I got back to Canada I figured out that I needed more help. This ride was going to entail more than me getting my bike over, jumping on the bike, and going for a ride. I reached out to this group in New York City, and they tentatively said, we're on board. Then I found a Canadian group called Victoria Hand Project out of Victoria, BC, that do 3D printed upper extremity stuff. And they were on board, but because of issues, they couldn't commit financially to it.

When they couldn't commit financially, they kept asking me, what am I going to do? Am I going to give up? I was going to do this ride last year. I said, no, I'm not giving up. Regardless of what you people decide as organizations, I'm doing this. I got a bunch of Polish friends over there and a Brit that's willing to follow me in a vehicle and make sure I'm okay at the end of the day. And if need be, I'll sleep in schools, I'll sleep in barns, but I want people to see me ride. I don't know if it's my stubbornness or whatever. People that I used to work with in Ukraine two years ago came to me and said, we want to help.

So from that we got a Ukrainian Canadian filmmaker. Well, she immigrated to Canada a number of years ago to Halifax, and she's part of the team. And she did a promotional video which is on YouTube. And we've got the commitment for logistical support, if not financial support for the ride. The most expensive things were handled, will be handled with another American group. If I may mention these groups by name?

Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, please.

Jakob Kepka: The American group that repurposes prosthetics is called Penta Prosthetics out of New York City. When I came back a year ago, I shipped 16 boxes of used prosthetic parts that I tore down that were donated to me from two clinics here in London.

Jeff Tiessen: Well, you've got quite a support system.

Jakob Kepka: Yeah, it's just to get the word out and get the money in. Right?

Jeff Tiessen: Well, I remember with Man in Motion, Rick Hansen's around the world tour, it didn't really start seeing donations until he got back to Canada.

Jakob Kepka: That's our hope.

Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, and the momentum started. So, I guess there are some miles you need to cover, figuratively and literally.

Jakob Kepka: Stephen, the Brit that will be driving, he's now the leading force and dealing with NGOs and promotions and, I'm just the guy riding the bike. I'm probably the least important aspect of this. Logistically, the most important aspects of this ride are the Ukrainian amputees, both civilian and military. Our hope is for the ride to generate interest after. They'll be filming me as I ride, which will be probably little snippets of me getting on and off the bike at the end of the day. Who wants to follow a one-legged cyclist for 6 hours? But more importantly, we'll be doing stops where we can to highlight the lives and experiences of the actual amputees in Ukraine.

Jeff Tiessen: Talking about amputees, you being one yourself, as you mentioned an above knee amputee, I just wanted to touch on that briefly because that's an interesting story as well. You were in the military, injured, and stop me when I get this wrong, honorably discharged for medical reasons, and then fast forward 30 years, and you still have that injured knee, and then you chose electively to have it amputated.

Jakob Kepka: Well, what happened was I was in the military. I had an injury that resulted in me having a padillectomy. They removed my kneecap. I was infantry, and the military organization I was in has the philosophy that if you can't be an infantryman, you can't be in our organization. And I was forced to take a discharge, and I came back home to Canada, and that's when I took up cycling, because I couldn't run anymore. It was too painful. I took up cycling. I rode for a number of years. I would have surgeries on my knee. It was an injured knee on and off. But by about 1990, so this is from 1980s, early eighties to 1998, I couldn't ride a bike anymore. My condition got so much worse.

In 2001, I had my first knee replacement, June 2001, and by December 2013, I had my sixth. And at that time, just the last three were revisions in a 26-month period. I'd had enough, and there were complications, and I got my wish.

Jeff Tiessen: Well, I read that you said that your amputation led to a vastly superior quality of life than. I'm understanding what you mean by that, probably with the pain and the lack of function. But is there another level to that? Did it change your life in a different way?

Jakob Kepka: It made me more grateful and appreciative of what I have and what I'm capable of. Um, I look at it this way. My quality of life deteriorated from 1998, when I couldn't ride a bike. My psychological health deteriorated. I couldn't train as much, and I kept modifying my lifestyle to keep my training. I was an endurance athlete so I was trying to figure out ways to keep it up.

And as my knee got worse and we were trying these knee replacements, and you'd have the high of immediately after knee replacement, and you're doing well in rehab, and as the months progressed, my condition worsened. And they'd say, well, you've had so many surgeries, by this time, I'm looking at over 12 to 13 knee surgeries. You develop a lot of scar tissue. You got this issue mentally and physically. My quality of life just got really worse. And then all of a sudden, after the fourth failed knee revision, total knee, I begged my surgeon to amputate, and he refused. And we had a heated discussion about it, and I stormed out.

I suffered with the deterioration of the knee. And I went back to him. He said, let's try again. Are you willing to try again? I said, yes. And that one failed within a few months. And for years I was living on opioids, and I never abused them because they frightened me so much. I'd run into a doctor from eastern Europe, a former doctor who was an EMS, a paramedic here in Canada, because he couldn't work as a doctor. And he asked me what I was taking. This is when I had a leg, for my pain. And I told him. He said, you know, in my home country, we found out that caused a lot of psychological problems, extended use of these kinds of drugs, including anger management problems, which I was dealing with at the time. I joined the United States Marine Corps, where they take angry young men and make them angrier.

And my quality of life, every aspect of my life, even though I wasn't abusing the drug, was deteriorating. And then all of a sudden, I couldn't do what I loved, which was cycling. I rock climbed too, stuff like that, the more adventurous stuff. And I was in such a deep depression, I felt liberated when I had the amputation. You know, my first question to the doctor was, after the amputation, is the stump long enough for a prosthetic?

In the months I was in the rehabilitation hospital in Toronto, I worked hard to walk out of there well. And then I was awarded the microprocessor knee. I worked hard on learning how to walk well. When you're in a rehab hospital, they ask you what your goals are as an amputee. And some people say, you know, drive a car again, play with my grandkids. Mine was get on a bike again.

Jeff Tiessen: How long did it take you?

Jakob Kepka: Well, I didn't know how you do it. I was living in Oshawa at the time, and a friend of mine took me to my idea of eye candy, which was to a bike shop, a high-end bike shop in Whitby. And I'm in the bike shop looking at all these bikes, and the bike shop owner had – and this is right after the London Paralympics - back issues of a European cycling magazine, and in one of them was an article on the Spanish amputee para-cycling team made up of amputees from Barcelona. And they were AKs, the two champions. Juan Mendez, who was a Spanish champion. They ride without prosthetics. So I go, well, you know, that's an idea.

I didn't like the idea of wearing a prosthetic being tangled up in a bike. And my stump is relatively short. I didn't have money for a bike at that time. And fortunately, somebody told me about the Challenged Athletes Foundation from California. And being a marine, I get a little bigger grant than civilians do through their Operation Rebound, which allowed me to buy my first road bike. My prosthetist in Whitby made my first cycling pod attachment to my bike for free. It took me three years of riding on the road, badly, till I got the hang of pulling up on the pedal. I even made a trip to Barcelona and trained with them for a few weeks. Last year, I'll say it in miles, because I'm old fashioned., I did about 14,000 miles last year.

Jeff Tiessen: Wow. So that's crowding 20,000K probably. That's incredible.

Jakob Kepka: Yeah. I was doing, on average, in a week, 900 miles.

Jeff Tiessen: You are a resourceful man. There's no question.

Jakob Kepka: I don't know if it's resourcefulness or just being bloody stubborn.

Jeff Tiessen: That’s got to be part of it too. And it serves you well, Jakob, that's for sure. Listen, before I let you go, I just want to know, with a lot of your time on the bike I understand, but when you're not training, what fills the other hours, if there is such a thing in your life?

Jakob Kepka: There aren't many hours left after when I'm training, even in the winter, my workouts, preparing for this ride, five to six hours of cardio, sometimes more. Fortunately, you get to eat a lot and not gain weight after that kind of workout. I eat a lot. I read. I've been asked to participate in another kind of physical challenge in 2025, which we're recruiting amputees for, which is to climb Mount Orizaba in Mexico in November 2025, an amputee team through an outfit in Elor0a, Ontario.

I've always wanted to do mountaineering. I do rock climbing. I tried ice climbing with the outfit in Elora. And now mountaineering, that's another thing off my bucket list. It might be the, you know, the culmination of my bucket list, because if things go wrong, but at least I do it.

Jeff Tiessen: Do you even refer to these years as your golden years?

Jakob Kepka: No. I've had several surgeries post amputation, you know, stump revisions and the osseo-integration. I've had issues with phantom pain where we did nerves interfaces, and I always end up in a rehab hospital and I continue. I've always gone back to the same rehab hospital in Toronto, and they accept Jakob as Jakob, just let him go in the gym and let him do his thing. I'm talking about West Park Healthcare because they have their own amputee wing, and we're like a little community. We have our own physio gym and our own physios there. They would come to me and go, you're so inspirational. You work so hard and you walk so well. And I go, no, I'm not the inspiration. This is just who I am. It's who I have been since I went into Marine Corps. They repurposed me, they reprogrammed me. The marine Corps exposed who I really was and my capabilities, and I latched on to it.

I said, the real inspirations are you people. When you do a 180. I'm doing what I'm meant to do, what I've done for almost 50 years. But when you come in here and you're frightened by your health condition or a traumatic accident, and you decide at this moment I'm going to turn my life around 180 degrees and live a healthy lifestyle and exercise, you are the inspiration because you're doing something that's scary.

Jeff Tiessen: That's a really good point, because we all have our own experience, our own story to tell, our own fears. Right? And, our own success stories that need not be measured against other people, like cyclists like yourself.

Jakob Kepka: Well, they were the inspiration to me. You know, I'm no different. A fish needs water to swim. Well, I need challenges and that stuff to breathe for my existence. These are people that are going contrary to their makeup, physical, mental makeup, and doing a 180 psychologically and physically, and they're overcoming hurdles that I haven't had to deal with for decades. Anxiety and fears that are associated with that. And they are the inspiration. Common people doing uncommonly challenging things, you know, that is totally against their makeup.

Jeff Tiessen: Well, yeah, and you know with a traumatic injury, not where we expect it to be all of a sudden. So, yeah, your ride is, if it's not inspirational, it's motivational.

Jakob Kepka: All I want to do is let people know that there is hope, and physical limitations are also a doorway to express yourself in new and glorious ways.

Jeff Tiessen: Wow. What a way to put it. Listen, before I let you go, I want folks to know where they can find the video, the ride video. I've watched it. It's fabulous. And I'm sure the film work and the content that's going to come back from Ukraine is going to be equally as good. So, the name of that YouTube video so people can look that up?

Jakob Kepka: It's under Hoperaising Expedition. Hoperaising is one word, and it's on YouTube. You get a little idea of what motivated me to think about the ride and how I train during the winter. It's all cardio. There's nothing spectacular, just long hours staring at handlebars on a spinning bike or on an elliptical. It's great for my reading because I read when I do these things.

Jeff Tiessen: It's not glamorous is what you're saying, but the video is really good. So, with that, thank you so much for joining me. And I know it was short notice, but I knew time was tight before you left. We wish you all the best, safety and health, and for your purpose, too. I really think that when the momentum picks up in Ukraine and when you get back to Canada, it's going to make a remarkable difference in people's lives. So with that, I say thank you Jakob. Thank you all for being with us today. This has been Life and Limb. Thank you for joining Jakob and I. You can read about others who are thriving with limb loss or limb difference and plenty more at Thrivemeg.ca. Until next time, live well.

Jakob Kepka: Thank you, Jeff.

Jeff Tiessen, PLY

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?