Life & Limb - A monthly podcast about Living Well with Limb Loss

Prosthetist-Patient Perspectives with Marty Robinson

Episode Date: July 10, 2024

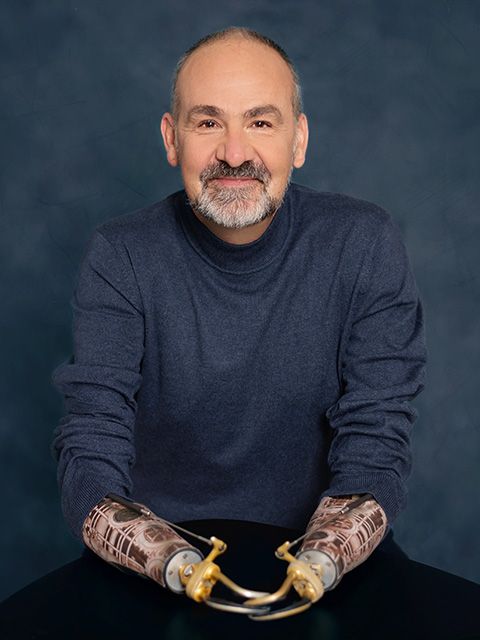

Prosthetics is an intriguing profession. It’s science. It’s art. And it’s social science in terms of relationships that are cultivated with patients or clients who, by way of life’s circumstance, may be hard to please at times. With over 35 years of experience with patient-prosthetist relationships, certified prosthetist Martin “Marty” Robinson provides some perspective on these "partnerships."

Episode Transcript

[00:00:04] Jeff Tiessen: Welcome to Life and Limb, a podcast from Thrive magazine all about living well with limb loss and limb difference. I'm Jeff Tiessen, publisher of Thrive magazine and your podcast host.

Let's get right to it by introducing my guest, Marty Robinson. I've known Marty for about 30 years, and we actually see each other quite regularly, almost monthly for a couple of hours in his clinic. He is my prosthetist, and with only a brief interruption when he left the hospital clinic where he was working to go work for Ottobock, when he returned with a private practice of his own, I quickly joined his client list. And here we are 35 years later. Marty, let's start with when we first met, and it was the bar, and not a bar, the bar at your sister's wedding. I was the plus one, my wife being a nursing college friend of your sister Julie. And I remember, well, I think you were staring at me, saying something maybe a little awkward or strange, but you quickly qualified to say, hey, I'm a prosthetist. And that made sense of what you had had just said. So first, how are you? And second, do you remember that?

[00:01:32] Marty Robinson: Oh, absolutely, Jeff. Well, thanks for inviting me on the podcast.

Actually, we've known each other, if we count that as the initial meeting, 36 years. Yeah, I remember the wedding. So, you and Brenda were invited to the wedding, and I was staring at you because you were grasping two very fine glasses filled with a delicious elixir. I think it was beer. And I was quite enamored with your skill level, so I was staring, but more from an appreciative, like, wow, that guy is very good at that. Right? And I think I said, is one of those for me? And you quickly said, no.

And I think I approached you again later and, you know, introduced myself as Julie's brother, and that I was in prosthetics, and I was quite interested in the field in general. I love you, by the way.

[00:02:37] Jeff Tiessen: Oh, thank you very much.

[00:02:39] Marty Robinson: We’ve become really good friends. I think people should know that.

[00:02:42] Jeff Tiessen: We certainly have. When you see an amputee with prostheses that you didn't make, do you wonder who made those. Like, sort of, what is he wearing?

[00:02:55] Marty Robinson: Yeah. Who is he wearing? Yeah, it's sort of like the fashion industry, right? But there's a respect, too. We've learned to not judge too much, but sometimes people can be very critical and say, oh, geez, I wonder who made that. You know, that's a piece of junk or whatever. Well, you never do that because you don't know the full story. Right. There could have been a long, arduous process with getting to that level and achieving that fit. Yeah, we're always very curious of each other's work, for sure.

[00:03:31] Jeff Tiessen: That's interesting. I was at a gas station once, and I was wearing a really old beat-up pair of what I called my farm or barn arms. And I know there was some duct tape holding a little bit together. And young guy, I think he was pumping the gas, asked me if I made them myself. And I never told you that because I thought that would be such an insult.

[00:03:52] Marty Robinson: Yeah, thank God for duct tape. We all have to use it. But I mean, you know, when you think about the field Jeff, I mean, a lot of the great inventions and even some of the quick fits fixes are done by the end user themselves. A lot of the stuff that has become mainstream actually comes from people that use prosthetic devices, who have then become innovators in the little quirky changes and really interesting developments, all the way to, like, TRS with Bob Radocy. I mean, an engineer who had a trans-radial below the elbow amputation, not happy with what's available, and so he ended up developing his own line of goods, which became an international hit and still is today. So, yeah, it's important to learn from the end users. Like today, I was in clinic, and one of my patients needed some advice on how to adjust the socket that was tight in the bottom and loose at the top. And I said, well, one of my clients talked to me about half socks. Would you like me to tell you about half socks? I mean, it seems like such a simple thing, but it's a great solution for everyday problems that people have to deal with, right? So it's kind of cool too.

Everyone thinks of these sophisticated designs and developments, but there's many cool things that have come just from people who use prosthetic devices and come up with their own fixes, which then get transferred back to the prosthetist, who then shares it, hopefully with other users.

[00:05:30] Jeff Tiessen: Probably one of the best examples is what was formerly known as Flexfoot, the Ossur Cheetah that was developed by a lower extremity amputee. Van. Van Phillips, maybe?

[00:05:42] Marty Robinson: Yeah, Van Phillips. So again, sometimes if it happens to be somebody that has some, you know, either biomechanics or engineering background, and they happen to have lost a limb for whatever reason, and then just take an interest in that. Which Van Phillips did, and look at how that turned out. Look at what that boomed into.

It's amazing, really. And you can give many examples. Another good one is the Total Knee. The Total Knee is a polycentric knee joint that has become very popular in the field. Actually, it's one of Ossur's offerings now.

It was developed by the father of a girl, a young girl who had lost her limb to, I believe it was cancer. He was just looking for a smaller, more geometric type of knee joint that folded up on itself. She had a very long limb. And so he came up with this design, which then became a product. So, I think the more you look into the industry of prosthetics and orthotics, there are a lot of really cool stories like that.

[00:06:56] Jeff Tiessen: I'm sure. Let's jump into the field of prosthetics. And it intrigues me, knowing you intimately in the sense of how a prosthetist and a patient relationship, client relationship, works. I mean, it's science, it's art, it's social science, when it comes to those relationships. I want to ask you how and why you chose this profession, but let's start with, what was your first job? Way before being a prosthetist, maybe as a teenager. Where did you start?

[00:07:31] Marty Robinson: That's a great question. And one that I think about a lot, because I remember applying for this job. It was in the paper in Woodstock. I grew up in Woodstock, Ontario.

From grade six on, I lived in about five different other small towns before that, but ended up in Woodstock. And there was a job for a stock boy. Not stock car boy, but stock boy. They were specific. You had to weigh at least 140 pounds and be able to pick up and move something like 75 pounds. I weighed about a buck 15.

I could maybe lift 15 pounds. But I applied for the job anyway, and I was lucky enough to get that job. They gave me a shot, and that was a great job because that was when they were still weighing out nails for clients. Right? In the back room. And the stock boy had to do anything and everything. And I loved it. I mean, they just came back and said, we want you to paint the back room. I had no clue how to paint, right? And I started painting They kind of guided me through it, and all the way from writing one's names on the Styrofoam cups to filling it and getting everyone's order and stuff like that. So, there was a social aspect of it. But I really loved one thing being a stock boy; I loved the interaction with customers. I craved it. So, I realized about myself that I really like that kind of responsibility, you know, working with somebody and finding and working on a solution.

So that was my first job. Good segue, though, would be another job in high school. This is before they disbanded hospitals for mentally handicapped. They used a lot worse terms back then, but for anybody that was incapable of living on their own. Some of these people were dropped off as children. They were perfectly fine people, but they were dropped off as children, to be institutionalized. So, it was an institutionalized place where people of all levels mental handicap, and they needed assistance with taking care of themselves. I got a job working in the Tuck Shop. And again, I loved it, the interacting with people. And, I just really, really got a charge of that. So it kind of steered me a little bit I guess, feeling like a connection to anybody that maybe is looked upon differently from other people. And I just really had a different way of engaging with everybody. Like, in that situation, I just feel that I connected much quicker and was a little more passionate and compassionate.

[00:10:57] Jeff Tiessen: So for your prosthetist job, you saw a job posting for certified prosthetists? Like, I don't remember that being on the aptitude or the guidance counselor list when you and I were in high school?

[00:11:09] Marty Robinson: Iin school in 1970s, I didn't even know what it was, Jeff. I mean, I wanted to be a phys. Ed. teacher at a high school. I love sports and all that kind of stuff, and a couple of my buddies were going down for Guelph’s March counseling, which was an investigation into what courses Guelph offers. Well, they had one in human kinetics.

Again, didn't know anything about it. Really kind of caught my interest, and I really went along just as a comrade, because we're going to do beers after. And it was like, oh, yeah, let's go check it out. Ended up being fascinated by it. Went back, changed my transcripts, put Guelph on top, and luckily got into Guelph, and that was a four-year adventure. Loved it.

But again, human kinetics on its own, or kinesiology on its own, isn't always there with completion of your education. It's a stepping stone. A lot of my ex-classmates got into physiotherapy. Some of them became doctors. A few of us got into prosthetics and orthotics, and that was, thank God, because we got a course in third year which was about prosthetics and orthotics, which caught my interest. So after I graduated, I was like, hmm, how can I apply my kinesiology degree? Not enough people knew about it. You know, what the impact or even what you do?

So, anyways, yeah, I started looking at prosthetic orthotic opportunities in the field, and luckily, it just, like a lot of times, by chance, if you're lucky you'll find it. And somebody had canceled in the co-op position at Hamilton, Chedoke McMaster. And last minute, the guy was like, can you start a Monday? There's a physician who pays minimum wage, and I'm like, I'll be there. And so that, for me, was the start of all of this. And I just walked in that first day, and was like, yeah, this is for me. Like you said earlier, art and science collide, and it's just a great combination. If it suits your personality, which it did for me. There's the patient contact part of it, but there's also the puttering and problem solving, and not everything's perfect, but you got to find it to work out a solution.

[00:13:53] Jeff Tiessen: Well, on that people part that you talked about loving so much at the Tuck Shop and being the stock boy, there's a whole lot of that in what you do now. And we come from all walks of life, amputees, all facets and diversity in it. And, you know, some of us are still having a hard time. Some are not. Some might be hard to please, be it a new amputee or a seasoned one. Some might be critical of your work. So how do you manage that? How do you find that balance? Where are the boundaries?

[00:14:29] Marty Robinson: Yeah, that's a great question. That's the toughest. That's the toughest part. And I still not struggle with that.

I think you have to just remain humble. As my dad always used to say, you're only as good, and you've heard this said by many people, you're only as good as your last, whatever. So, I mean, prosthetics, to me, the beauty of it is that it's always morphing and changing. It's always about the person. Everyone's different. For me, it's about figuring out the person, and there is a person there. I'm fitting a person, not a stump or a residual limb. I'm fitting the person. So, the more time you take to understand and learn and appreciate what they are looking for, and they will guide you. Like, if you work together, you're going to get there. So I think it's like in many professions, I think listening is really key.

We definitely could have had more psychology in our training. We're kind of armchair psychologists in a way. But I think on the job, you learn, and I've become better at it. I used to over promise and under deliver in the beginning because I wanted to fix everybody and everything. Oh, yeah. Oh, you want to rock climb? No problem. Oh, you're 85, you've never rock climbed before? No, we'll get you rock climbing. But, you know, that's a bit over the top. So, I think it's all about setting expectations that are realistic and really finding, searching the individual's needs in a sense of what's going to get them the most satisfaction in their life again and get them back to where they were. They feel good again about themselves. Their self image is going to be restored as much as possible. I mean, again, that's expectations. But that's the part that intrigues the hell out of me, Jeff.

[00:16:37] Jeff Tiessen: When one of us, me, being a double-arm amputee, aren't happy with your work, not to say that's your fault but can we come to, do you take that personally? Are you sensitive to that?

[00:17:02] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I think so.

But I think that's what makes you better, too, because if you don't take it personally, then you don't try to improve. But I think initially, I would take it personally to the point where I, you know, would take it home with me and I would really let it get in my head and that kind of thing. Now, I take it personally, but I always try to think, okay, you know, a person's telling me something. It's like anything; it's hard to take criticism. Right? But if you can understand that, take the criticism, the direction of the criticism. Some people give it a little harsher than others. But again, I don't want people to suffer in silence. Like, if someone's afraid to tell me that it's not working, I'd rather that they come in and say, listen, I'm not happy with the way this turned out, or it never really felt like it fit right from the beginning. It gives me a chance for redemption. You can try to make it better.

And most people, you know, 99% of the time, are very, very patient with, and we're very patient with them. It becomes a give and take thing. And when you get the give-take thing going on, that's when you really can get stuff done. And you and I have been through that, Jeff. You're very understanding. I mean, there's times when I've let you down, and I acknowledge it, and the thing is, it makes me want to not do that again.

I don't want you to lose another. I want you to get that teddy bear next time at the exhibition. I don’t want your hooked cable to come flying off.

But, yeah, that's a really good question. I think a lot of us struggle with it. And again, it's personalities, personality of the prosthetist. Sometimes you're going to meet people you just don't jive with. So, one out of 100 times, it probably doesn't work. And maybe sometimes you, they, have to go somewhere else, and they acknowledge that, or I acknowledge that I've done my best and we don't see eye to eye. Maybe it's me. You know, there are a lot of good people out there you could check out, but in most cases, you can work it out. And it's just a matter of, like I said, give me a little bit and I give you a little bit. It's that give and take thing. And it takes a lot of patience on both sides, for sure.

[00:19:30] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, nice. Really nicely said. Balance and compromise both ways. Let's switch gears a little bit to prosthetic repairs and the bane of my existence. And I'm going to give you a second to think about this as I remind you of a story of how surprised you were one day of the state of disrepair that I showed up in at your office. So, I'm going to ask you about surprises that people have come in with. Complete train wrecks of your good work. And the one for me was that I totally destroyed an elbow, bent a hook straight. And when you asked what happened, I told you, my horse dragged me across the backyard, and the only way for me to let go of that rope that I was hooked into, literally, was for the elbow to just crush and the hook to bend itself open. I'm sure there are even better stories. Is there anything that comes to mind?

[00:20:32] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I mean, it's life, right? You're living your life, and stuff is going to happen, and the prosthesis is going to take the brunt of some of it. We've seen all kinds of different home remedies to deal with broken parts. Probably the most recent and first time I've heard this was a gentleman who was ice fishing and walking out to his hut he walked over a hole that had been recently frozen, maybe the day before or whatever. He didn't see it. It was on his prosthetic side. He's a below the knee amputee. And skaboom. His prosthesis went into the hole and he yanked his leg out, and there was no prosthesis attached anymore. So if anyone from War Amps is listening, this is a true story. We actually told the truth to the funding agencies to say, we need to get this gentleman a new prosthesis. He did nothing wrong, other than was the victim of a little hidden ice fishing hole.

[00:21:43] Jeff Tiessen: These things happen.

[00:21:44] Marty Robinson: These things happen. We've seen people, for example, use the prosthesis to put out a fire that was happening in their house. And the prosthesis became a, you know, casualty of that. And you know it’s true when someone brings in a melted limb. The hand is melted and the glove is melted. But then I've had some people say, thank goodness it was my prosthetic leg. They got in an accident, and if it had been there, they would have been really severely injured. But, you know, it's a part that we can replace. We can restore that, so. But, yeah, there have been some interesting fixes, too. And some people, again, have come up with some brilliant, brilliant ideas to fix stuff. Really creative, let's say, like sewing stuff up. I saw this woman recently, and she must be a seamstress, honestly, sewing her prosthetic sleeve that holds the leg on.

I hadn't seen her during Covid. Covid kept people away from us for a long period of time. So, she came in after Covid, and needed to get a new sleeve. But in the meantime, it had torn and she had sewn it up every single little tear and rip. It was like a quilt. I was like, I don't really want to throw this out. It was like a piece of art, you know, so well done. And she had taken the time to keep this intact. Yeah, things like that.

[00:23:34] Jeff Tiessen: There's got to be so many. Speaking of taking the time, here’s a question for you. Why does everything related to prosthetics seem to take so long? Getting limbs made, waiting for parts, waiting for repairs in the clinic. What's up with that? Share with us. Why should we be more patient?

[00:23:58] Marty Robinson: That's definitely a chronic problem. But I think that, you know, we're guilty, too.

Again, it's about expectations. There are some timelines that are not as tight as what people would maybe expect and maybe have been told. So, again, it goes back to establish a relationship with your prosthetist or orthotist, right from the get go and get an idea of timelines.

And some of us are bad at just starting something and then putting it aside and not finishing it. Well, for me, the main thing is having a realistic turnover for things like casting and first fitting two weeks later.

Having some sort of cycle. And that's what I recommend to my colleagues and that's what we try to do. But I think, again, things do take longer than what people expect.

There's definitely the need, I think, for more of us doing what we do. I think that we could have a better turnover if we had, you know, more bodies involved in doing this. And I'm not pushing this back on the government, but, for example, in Ontario, we haven't had a raise for 14 years, so the pay has stayed put. And I think if we could afford to have more people doing this, we could turn things over quicker. But again, I think it comes down to you don't want to disappoint people say, oh, I'll have that ready for you next week. And then, and you know, four weeks later they still haven't had a call. Well, what I try to do is say that I can deliver on a two-week schedule and I try to really maintain that and I think that's realistic.

[00:26:05] Jeff Tiessen: You talk about expectations, so along the same lines, advice for amputees, but maybe new amputees particularly who don't know your expectations, and don't have any context or experience for their own What advice would give to new amputees about that? About new fittings and new technology, maybe? How do you put a blanket or put your arms around that?

[00:26:37] Marty Robinson: I think it's educating people because, I mean, it's the fear of the unknown. That's the way I always think about it. You just don't know what's coming up.

For example, two weeks ago I was in Guelph and we had a brand new amputee. Young gentleman, 41 years old. This is a traumatic event in his life. And you could tell he was hurting. I had another gentleman who's in his sixties who had been an amputee of the similar level. And I was like, hey, do you mind just talking to this guy even for a few minutes? And, the amount that this guy got out of that connection was huge.

So, I think things like that. I giving people a good guideline and timeline of what, how things are going to go down and that there is hope that the prosthesis can really provide you with a lot, a lot of function and mobility that you've lost. And, yeah, I think it's answering questions, engaging and informing. People want information at that stage. They're lost. A lot of times they haven't been talked to that much in the hospital. I'm surprised at that. So we like to give them little bit of a window to look ahead, a little bit of forward thinking on what's coming up, and that encourages them. They're always surprised to think, oh, I'm going to be walking in two weeks. Yep, we're casting you today and you're going to be up in those parallel bars walking in two weeks. And they're like, oh my God, really? And I'll bring the Kleenex, even for me, 35 years later. The best part is when you get someone going again for the first time. Somehow you share their joy and hard work. We ask people, are you up for this? This is gonna be a lot of hard work, but we're gonna work together and we're gonna get there. So it's encouraging. It's informing. It's a lot of coaching and there's a lot of people who are involved, and I share in their energy and my energy with them, and, man, I get a lot back, too. So, it's fun getting someone going the first time.

[00:29:17] Jeff Tiessen: Oh, I'll bet it is. And that's really cool to hear you say that, that it's not a production line in there. There still is that human connection. And yeah, I would imagine 35 years in the business and working with people, you're learning all the time, let alone about the new technology that is always coming out. So, if you had to think back to when you started and what you know now, is there one thing or a couple of things that you wish you knew when you started in the profession that you know now?

[00:29:52] Marty Robinson: Yeah, that's a good one. That's deep. I think I wasn't aware of how much I could push myself to do more, to get deeper with any problem that might exist, because there is technology, lots of technology available, but it's not even about that. It's about, for me, not being afraid to make the connection. Connection and the commitment. I guess that's what I would say that I learned from when I started out at Chedoke, when I didn't know anything and was motivated and excited about everything, but didn't really know what I could offer and how far I could extend that. But now I guess it's the confidence, knowing my limitations and knowing how far I can push myself to push somebody else.

[00:30:54] Jeff Tiessen: And you mentioned earlier, too, about not over-promising. Yeah?

[00:30:59] Marty Robinson: That's a really big part of it, too, the expectations, like defining things in the beginning when you're starting a new project, a new commitment with somebody, and really being honest. Not everything's positive. I think it's so easy for us to get somebody all pumped up, and then sometimes they're let down because we kind of oversold it. And I think anyone would appreciate the real story and the real picture. And it’s important that they know that a big part of it is their commitment and their energy in the project too. Like, you're going to work hard, and you're going to get a lot out of this. I'm going to do my best for you. The therapist is going to try to really be engaged in helping you learn how to get off the floor and how to do all the different phases of gait and what kind of training and exercises you need to do to prepare for that. But, yeah, I think laying it out in the beginning and being very honest is really important. And you know what I learned too Jeff, is now I take more time in the beginning of starting a project. Before I was in such a rush to get on with it and get going, and I felt that pressure of getting things done, that sometimes I didn't take the time to really figure out where I was going and what was the plan and what are we doing here? Like, get as much information in the first couple of visits with a new client as you possibly can, because once that person leaves your clinic, then you're speculating at that point. Some information is lost. So, yeah, I just take more time in the beginning to really, really, get as much information and as much detail that I need to make decisions on what kind of foot to go with, what type of socket style. Maybe back in the day I wouldn’t have, but when I see the way you live your life, I'm like, that wouldn't have made any sense. But I couldn't have imagined that at the time. It seemed like more is better or more expensive is better. Well, that's not always the case. So, yeah, I think just slowing down the beginning. I worked with a German colleague for a few years when I worked with Ottobock, and he had a great approach. He was never in a hurry to go to the next step until you're completely happy with the step that you're at. And, you know, from having sockets fit and that's usually the check-socket stage, do not go to finishing the socket until you're 100 percent confident that you're there. Do another check socket. Take another fitting. It's not that much.

[00:34:08] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, but you've got us wanting you to rush. We want stuff done quickly.

[00:34:15] Marty Robinson: Yeah, and sometimes we both collectively suffer from that approach because what happens is it could be better. It could have been, you know, a better end result, and it does take time.

[00:34:30] Jeff Tiessen: Do you ever think about what you might be doing if, you know, this prosthetist profession didn't work out for you? Aside from tuck shop work?

[00:34:42] Marty Robinson: i don't know. I like teaching, so I did teach for a while. I taught at Guelph. I taught at the college in prosthetics. I got a lot out of that. I think I would have liked teaching.

But this is special. You know, people ask me, hey, what would you have done if not this. I say, I would have done this. It sounds so cliche, but for me this was the perfect fit. This is a job that I don't have to get psyched up for. I'm 61. I'm not ready to retire. People are asking me about retirement. Sure, I think about retirement but I'm not ready to. I feel like I'm not done yet. I'm still enjoying it, and it's different every day. And it's that challenge. It's the human connection.

There are so many relationships that you establish. It's a pretty intimate type of relationship too. This is different than helping you pick out a pair of jeans. This is way beyond that.

This is part of your self image and your mobility or your function, in your case Jeff. I mean, we know you've got to have three sets of prostheses going at any one time, or it's going to mess up your day, your week, your month, your trip, your whatever, right? So it's very, very important to realize that.

[00:36:22] Jeff Tiessen: I've had a chance to speak at some of your profession’s conferences and I've talked about pulling back the curtains on our lives, as we pull back the curtains on your profession here, but I talk about those couple of hours we spent together a month, and all my other waking hours are dependent on the work that you did in those couple of hours.

[00:36:48] Marty Robinson: Yeah. And I take that seriously. And I think anybody in the profession, if they don't, then they're going to fall short. People say, you got to leave your work at work, and a lot of the new thinking is you work to live, and, well, okay, I get that. But when I'm at work, I take it seriously… the impact of my actions. I've gone to people's homes. I mean, my family would even say to me, why do you do that? I go, I don't know. I just have to; it's just that it's important to me. It's not just about leaving it at work. It's in a pinch. I mean, I can't do it for everybody, but if somebody called me and said, listen, I'm, I'm going to Cuba tomorrow, and my foot's facing north and it should be facing south and I have to take an hour or two hours out, why wouldn't I do that? Okay, I don't want everybody be calling me right now.

It gives me peace. I don't know. It's just something that I've always done, and it's my personal decision. I wouldn't recommend that for everybody. Not everybody's into that, but for me, I always kind of felt like I would be available if really needed.

[00:38:30] Jeff Tiessen: Should we give your phone number right now?

[00:38:32] Marty Robinson: Yeah, sure. But that's the honest truth, though. I've always just been that kind of person. And my parents were like that. And, you know, it's just nice to find a profession where you can satisfy that little part of you, that little cell in there that you get a buzz from going that extra little distance. And there's so many people in this field that are like that. I'm not sure why? Maybe that’s why they got into this.

[00:39:12] Jeff Tiessen: Last one for you. And this is what I'd like to ask everybody who joins me as a guest. So, a great day for you. If that's the recipe, what ingredients go into making for a really good day for you?

[00:39:30] Marty Robinson: Great day. Hmm. Well, we have to keep this PG.

[00:39:38] Jeff Tiessen: Not a bad idea okay.

[00:39:40] Marty Robinson: Well, I love the outdoors. So, a great day for me would be to start by doing something a little bit physical outside. I would love to have my family around on that day. I love having my family close. We do a lot. We still do a lot together.

I don't know. That's a pretty good question, because I'm almost saying I'll get in my car and go to work, but is that bad?

That's why I'm struggling with retirement, because I don't know what I'm going to do. You can only make so many mediocre birdhouses, right? I mean, there's not a huge market for it. It would involve people. I like having people around. I like my private time after work. I get a big fix at work engaging with people. So at some point in the perfect day, I like to engage with people who are close to me.

I like to laugh. I like to make people laugh. I'd like to travel more, a little bit more. So the perfect day would probably be in a different location or a place I've never been to been before. Meet some people that have a different culture.

You and I have been to Belize together. Those kinds of experiences. Well, I think I might have had a perfect day there. Just the feeling of being in a different place where you've helped some people that would normally not have a prosthesis.

[00:41:19] Jeff Tiessen: For context for everyone, that was sort of a working trip, but you were helping some folks in a very poor village that had no access to prosthetic care with not just donated componentry, but your time and your expense and how appreciative they were of that. That's not what we were looking for. It was to help them for sure.

[00:41:46] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I'm appreciative to you for including me in that trip. That's a highlight. One of the highlights of my career actually was doing that.

[00:42:09] Jeff Tiessen: And maybe a home prosthetic visit to someone, to someone's home to help out a little bit?

[00:42:15] Marty Robinson: Well, I swear, if I could have the airstream trailer with the prosthetic clinic in the back and just travel around and still do what I do, because I do love this. I say to some people, hey, this is the only thing I'm good at, right? So, it's Marty's Mobile.

[00:42:37] Jeff Tiessen: I like it.

[00:42:38] Marty Robinson: I get a lot out of it. And that's important to me. There's a lot of satisfaction in the job. A lot of job satisfaction for sure.

[00:42:45] Jeff Tiessen: Wow, what a great place to end. And you've shared so much that I think all of us can kind of just go, hmmm. When it comes to our relationship with prosthetists, orthotists, and how you see it, your perspective. Because like I said, this is kind of pulling back the curtains for us. And when we're in that clinic room and off you go with our limb, we don't know what's going on back there and why it's taking so long.

[00:43:11] Marty Robinson: Don't be afraid to push us because we'll be better for it. And you Jeff, you've made me better because you've challenged me. And, you know I think that it's about honesty. And when you get a good relationship with your prosthetist, I mean, that's a pretty sweet thing because it's like I said, give and take, but we really want to provide as much as we can for you. As far as technology, there's so many great things existing right now that we can offer. But the only thing that hasn't changed is the patience and understanding and listening. Those things will always be important, whether we're getting 3D-printed devices or what have you, or A-I gets involved in some capacity, or osseo-integration which people are investigating. I think that the thing that will always be the same and always will be important is the human element and the connection. For me its what allows me to be a little bit better at my job, for sure.

[00:44:40] Jeff Tiessen: Sounds like that's what you really love about it. So listen, thank you. Thanks for all the insights and really poignant comments. And thank you to all of our listeners. This has been Life and Limb. Again, thanks to Marty Robinson, my prosthetist, and you know, a bit of a legend in the industry, in the profession, no doubt.

Check out previous podcasts and our upcoming guests on our website at thrivemag ca. And you can read about others who are thriving with limb loss or limb difference and plenty more at thrivemag ca, too. Until next time, live well.

Let's get right to it by introducing my guest, Marty Robinson. I've known Marty for about 30 years, and we actually see each other quite regularly, almost monthly for a couple of hours in his clinic. He is my prosthetist, and with only a brief interruption when he left the hospital clinic where he was working to go work for Ottobock, when he returned with a private practice of his own, I quickly joined his client list. And here we are 35 years later. Marty, let's start with when we first met, and it was the bar, and not a bar, the bar at your sister's wedding. I was the plus one, my wife being a nursing college friend of your sister Julie. And I remember, well, I think you were staring at me, saying something maybe a little awkward or strange, but you quickly qualified to say, hey, I'm a prosthetist. And that made sense of what you had had just said. So first, how are you? And second, do you remember that?

[00:01:32] Marty Robinson: Oh, absolutely, Jeff. Well, thanks for inviting me on the podcast.

Actually, we've known each other, if we count that as the initial meeting, 36 years. Yeah, I remember the wedding. So, you and Brenda were invited to the wedding, and I was staring at you because you were grasping two very fine glasses filled with a delicious elixir. I think it was beer. And I was quite enamored with your skill level, so I was staring, but more from an appreciative, like, wow, that guy is very good at that. Right? And I think I said, is one of those for me? And you quickly said, no.

And I think I approached you again later and, you know, introduced myself as Julie's brother, and that I was in prosthetics, and I was quite interested in the field in general. I love you, by the way.

[00:02:37] Jeff Tiessen: Oh, thank you very much.

[00:02:39] Marty Robinson: We’ve become really good friends. I think people should know that.

[00:02:42] Jeff Tiessen: We certainly have. When you see an amputee with prostheses that you didn't make, do you wonder who made those. Like, sort of, what is he wearing?

[00:02:55] Marty Robinson: Yeah. Who is he wearing? Yeah, it's sort of like the fashion industry, right? But there's a respect, too. We've learned to not judge too much, but sometimes people can be very critical and say, oh, geez, I wonder who made that. You know, that's a piece of junk or whatever. Well, you never do that because you don't know the full story. Right. There could have been a long, arduous process with getting to that level and achieving that fit. Yeah, we're always very curious of each other's work, for sure.

[00:03:31] Jeff Tiessen: That's interesting. I was at a gas station once, and I was wearing a really old beat-up pair of what I called my farm or barn arms. And I know there was some duct tape holding a little bit together. And young guy, I think he was pumping the gas, asked me if I made them myself. And I never told you that because I thought that would be such an insult.

[00:03:52] Marty Robinson: Yeah, thank God for duct tape. We all have to use it. But I mean, you know, when you think about the field Jeff, I mean, a lot of the great inventions and even some of the quick fits fixes are done by the end user themselves. A lot of the stuff that has become mainstream actually comes from people that use prosthetic devices, who have then become innovators in the little quirky changes and really interesting developments, all the way to, like, TRS with Bob Radocy. I mean, an engineer who had a trans-radial below the elbow amputation, not happy with what's available, and so he ended up developing his own line of goods, which became an international hit and still is today. So, yeah, it's important to learn from the end users. Like today, I was in clinic, and one of my patients needed some advice on how to adjust the socket that was tight in the bottom and loose at the top. And I said, well, one of my clients talked to me about half socks. Would you like me to tell you about half socks? I mean, it seems like such a simple thing, but it's a great solution for everyday problems that people have to deal with, right? So it's kind of cool too.

Everyone thinks of these sophisticated designs and developments, but there's many cool things that have come just from people who use prosthetic devices and come up with their own fixes, which then get transferred back to the prosthetist, who then shares it, hopefully with other users.

[00:05:30] Jeff Tiessen: Probably one of the best examples is what was formerly known as Flexfoot, the Ossur Cheetah that was developed by a lower extremity amputee. Van. Van Phillips, maybe?

[00:05:42] Marty Robinson: Yeah, Van Phillips. So again, sometimes if it happens to be somebody that has some, you know, either biomechanics or engineering background, and they happen to have lost a limb for whatever reason, and then just take an interest in that. Which Van Phillips did, and look at how that turned out. Look at what that boomed into.

It's amazing, really. And you can give many examples. Another good one is the Total Knee. The Total Knee is a polycentric knee joint that has become very popular in the field. Actually, it's one of Ossur's offerings now.

It was developed by the father of a girl, a young girl who had lost her limb to, I believe it was cancer. He was just looking for a smaller, more geometric type of knee joint that folded up on itself. She had a very long limb. And so he came up with this design, which then became a product. So, I think the more you look into the industry of prosthetics and orthotics, there are a lot of really cool stories like that.

[00:06:56] Jeff Tiessen: I'm sure. Let's jump into the field of prosthetics. And it intrigues me, knowing you intimately in the sense of how a prosthetist and a patient relationship, client relationship, works. I mean, it's science, it's art, it's social science, when it comes to those relationships. I want to ask you how and why you chose this profession, but let's start with, what was your first job? Way before being a prosthetist, maybe as a teenager. Where did you start?

[00:07:31] Marty Robinson: That's a great question. And one that I think about a lot, because I remember applying for this job. It was in the paper in Woodstock. I grew up in Woodstock, Ontario.

From grade six on, I lived in about five different other small towns before that, but ended up in Woodstock. And there was a job for a stock boy. Not stock car boy, but stock boy. They were specific. You had to weigh at least 140 pounds and be able to pick up and move something like 75 pounds. I weighed about a buck 15.

I could maybe lift 15 pounds. But I applied for the job anyway, and I was lucky enough to get that job. They gave me a shot, and that was a great job because that was when they were still weighing out nails for clients. Right? In the back room. And the stock boy had to do anything and everything. And I loved it. I mean, they just came back and said, we want you to paint the back room. I had no clue how to paint, right? And I started painting They kind of guided me through it, and all the way from writing one's names on the Styrofoam cups to filling it and getting everyone's order and stuff like that. So, there was a social aspect of it. But I really loved one thing being a stock boy; I loved the interaction with customers. I craved it. So, I realized about myself that I really like that kind of responsibility, you know, working with somebody and finding and working on a solution.

So that was my first job. Good segue, though, would be another job in high school. This is before they disbanded hospitals for mentally handicapped. They used a lot worse terms back then, but for anybody that was incapable of living on their own. Some of these people were dropped off as children. They were perfectly fine people, but they were dropped off as children, to be institutionalized. So, it was an institutionalized place where people of all levels mental handicap, and they needed assistance with taking care of themselves. I got a job working in the Tuck Shop. And again, I loved it, the interacting with people. And, I just really, really got a charge of that. So it kind of steered me a little bit I guess, feeling like a connection to anybody that maybe is looked upon differently from other people. And I just really had a different way of engaging with everybody. Like, in that situation, I just feel that I connected much quicker and was a little more passionate and compassionate.

[00:10:57] Jeff Tiessen: So for your prosthetist job, you saw a job posting for certified prosthetists? Like, I don't remember that being on the aptitude or the guidance counselor list when you and I were in high school?

[00:11:09] Marty Robinson: Iin school in 1970s, I didn't even know what it was, Jeff. I mean, I wanted to be a phys. Ed. teacher at a high school. I love sports and all that kind of stuff, and a couple of my buddies were going down for Guelph’s March counseling, which was an investigation into what courses Guelph offers. Well, they had one in human kinetics.

Again, didn't know anything about it. Really kind of caught my interest, and I really went along just as a comrade, because we're going to do beers after. And it was like, oh, yeah, let's go check it out. Ended up being fascinated by it. Went back, changed my transcripts, put Guelph on top, and luckily got into Guelph, and that was a four-year adventure. Loved it.

But again, human kinetics on its own, or kinesiology on its own, isn't always there with completion of your education. It's a stepping stone. A lot of my ex-classmates got into physiotherapy. Some of them became doctors. A few of us got into prosthetics and orthotics, and that was, thank God, because we got a course in third year which was about prosthetics and orthotics, which caught my interest. So after I graduated, I was like, hmm, how can I apply my kinesiology degree? Not enough people knew about it. You know, what the impact or even what you do?

So, anyways, yeah, I started looking at prosthetic orthotic opportunities in the field, and luckily, it just, like a lot of times, by chance, if you're lucky you'll find it. And somebody had canceled in the co-op position at Hamilton, Chedoke McMaster. And last minute, the guy was like, can you start a Monday? There's a physician who pays minimum wage, and I'm like, I'll be there. And so that, for me, was the start of all of this. And I just walked in that first day, and was like, yeah, this is for me. Like you said earlier, art and science collide, and it's just a great combination. If it suits your personality, which it did for me. There's the patient contact part of it, but there's also the puttering and problem solving, and not everything's perfect, but you got to find it to work out a solution.

[00:13:53] Jeff Tiessen: Well, on that people part that you talked about loving so much at the Tuck Shop and being the stock boy, there's a whole lot of that in what you do now. And we come from all walks of life, amputees, all facets and diversity in it. And, you know, some of us are still having a hard time. Some are not. Some might be hard to please, be it a new amputee or a seasoned one. Some might be critical of your work. So how do you manage that? How do you find that balance? Where are the boundaries?

[00:14:29] Marty Robinson: Yeah, that's a great question. That's the toughest. That's the toughest part. And I still not struggle with that.

I think you have to just remain humble. As my dad always used to say, you're only as good, and you've heard this said by many people, you're only as good as your last, whatever. So, I mean, prosthetics, to me, the beauty of it is that it's always morphing and changing. It's always about the person. Everyone's different. For me, it's about figuring out the person, and there is a person there. I'm fitting a person, not a stump or a residual limb. I'm fitting the person. So, the more time you take to understand and learn and appreciate what they are looking for, and they will guide you. Like, if you work together, you're going to get there. So I think it's like in many professions, I think listening is really key.

We definitely could have had more psychology in our training. We're kind of armchair psychologists in a way. But I think on the job, you learn, and I've become better at it. I used to over promise and under deliver in the beginning because I wanted to fix everybody and everything. Oh, yeah. Oh, you want to rock climb? No problem. Oh, you're 85, you've never rock climbed before? No, we'll get you rock climbing. But, you know, that's a bit over the top. So, I think it's all about setting expectations that are realistic and really finding, searching the individual's needs in a sense of what's going to get them the most satisfaction in their life again and get them back to where they were. They feel good again about themselves. Their self image is going to be restored as much as possible. I mean, again, that's expectations. But that's the part that intrigues the hell out of me, Jeff.

[00:16:37] Jeff Tiessen: When one of us, me, being a double-arm amputee, aren't happy with your work, not to say that's your fault but can we come to, do you take that personally? Are you sensitive to that?

[00:17:02] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I think so.

But I think that's what makes you better, too, because if you don't take it personally, then you don't try to improve. But I think initially, I would take it personally to the point where I, you know, would take it home with me and I would really let it get in my head and that kind of thing. Now, I take it personally, but I always try to think, okay, you know, a person's telling me something. It's like anything; it's hard to take criticism. Right? But if you can understand that, take the criticism, the direction of the criticism. Some people give it a little harsher than others. But again, I don't want people to suffer in silence. Like, if someone's afraid to tell me that it's not working, I'd rather that they come in and say, listen, I'm not happy with the way this turned out, or it never really felt like it fit right from the beginning. It gives me a chance for redemption. You can try to make it better.

And most people, you know, 99% of the time, are very, very patient with, and we're very patient with them. It becomes a give and take thing. And when you get the give-take thing going on, that's when you really can get stuff done. And you and I have been through that, Jeff. You're very understanding. I mean, there's times when I've let you down, and I acknowledge it, and the thing is, it makes me want to not do that again.

I don't want you to lose another. I want you to get that teddy bear next time at the exhibition. I don’t want your hooked cable to come flying off.

But, yeah, that's a really good question. I think a lot of us struggle with it. And again, it's personalities, personality of the prosthetist. Sometimes you're going to meet people you just don't jive with. So, one out of 100 times, it probably doesn't work. And maybe sometimes you, they, have to go somewhere else, and they acknowledge that, or I acknowledge that I've done my best and we don't see eye to eye. Maybe it's me. You know, there are a lot of good people out there you could check out, but in most cases, you can work it out. And it's just a matter of, like I said, give me a little bit and I give you a little bit. It's that give and take thing. And it takes a lot of patience on both sides, for sure.

[00:19:30] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, nice. Really nicely said. Balance and compromise both ways. Let's switch gears a little bit to prosthetic repairs and the bane of my existence. And I'm going to give you a second to think about this as I remind you of a story of how surprised you were one day of the state of disrepair that I showed up in at your office. So, I'm going to ask you about surprises that people have come in with. Complete train wrecks of your good work. And the one for me was that I totally destroyed an elbow, bent a hook straight. And when you asked what happened, I told you, my horse dragged me across the backyard, and the only way for me to let go of that rope that I was hooked into, literally, was for the elbow to just crush and the hook to bend itself open. I'm sure there are even better stories. Is there anything that comes to mind?

[00:20:32] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I mean, it's life, right? You're living your life, and stuff is going to happen, and the prosthesis is going to take the brunt of some of it. We've seen all kinds of different home remedies to deal with broken parts. Probably the most recent and first time I've heard this was a gentleman who was ice fishing and walking out to his hut he walked over a hole that had been recently frozen, maybe the day before or whatever. He didn't see it. It was on his prosthetic side. He's a below the knee amputee. And skaboom. His prosthesis went into the hole and he yanked his leg out, and there was no prosthesis attached anymore. So if anyone from War Amps is listening, this is a true story. We actually told the truth to the funding agencies to say, we need to get this gentleman a new prosthesis. He did nothing wrong, other than was the victim of a little hidden ice fishing hole.

[00:21:43] Jeff Tiessen: These things happen.

[00:21:44] Marty Robinson: These things happen. We've seen people, for example, use the prosthesis to put out a fire that was happening in their house. And the prosthesis became a, you know, casualty of that. And you know it’s true when someone brings in a melted limb. The hand is melted and the glove is melted. But then I've had some people say, thank goodness it was my prosthetic leg. They got in an accident, and if it had been there, they would have been really severely injured. But, you know, it's a part that we can replace. We can restore that, so. But, yeah, there have been some interesting fixes, too. And some people, again, have come up with some brilliant, brilliant ideas to fix stuff. Really creative, let's say, like sewing stuff up. I saw this woman recently, and she must be a seamstress, honestly, sewing her prosthetic sleeve that holds the leg on.

I hadn't seen her during Covid. Covid kept people away from us for a long period of time. So, she came in after Covid, and needed to get a new sleeve. But in the meantime, it had torn and she had sewn it up every single little tear and rip. It was like a quilt. I was like, I don't really want to throw this out. It was like a piece of art, you know, so well done. And she had taken the time to keep this intact. Yeah, things like that.

[00:23:34] Jeff Tiessen: There's got to be so many. Speaking of taking the time, here’s a question for you. Why does everything related to prosthetics seem to take so long? Getting limbs made, waiting for parts, waiting for repairs in the clinic. What's up with that? Share with us. Why should we be more patient?

[00:23:58] Marty Robinson: That's definitely a chronic problem. But I think that, you know, we're guilty, too.

Again, it's about expectations. There are some timelines that are not as tight as what people would maybe expect and maybe have been told. So, again, it goes back to establish a relationship with your prosthetist or orthotist, right from the get go and get an idea of timelines.

And some of us are bad at just starting something and then putting it aside and not finishing it. Well, for me, the main thing is having a realistic turnover for things like casting and first fitting two weeks later.

Having some sort of cycle. And that's what I recommend to my colleagues and that's what we try to do. But I think, again, things do take longer than what people expect.

There's definitely the need, I think, for more of us doing what we do. I think that we could have a better turnover if we had, you know, more bodies involved in doing this. And I'm not pushing this back on the government, but, for example, in Ontario, we haven't had a raise for 14 years, so the pay has stayed put. And I think if we could afford to have more people doing this, we could turn things over quicker. But again, I think it comes down to you don't want to disappoint people say, oh, I'll have that ready for you next week. And then, and you know, four weeks later they still haven't had a call. Well, what I try to do is say that I can deliver on a two-week schedule and I try to really maintain that and I think that's realistic.

[00:26:05] Jeff Tiessen: You talk about expectations, so along the same lines, advice for amputees, but maybe new amputees particularly who don't know your expectations, and don't have any context or experience for their own What advice would give to new amputees about that? About new fittings and new technology, maybe? How do you put a blanket or put your arms around that?

[00:26:37] Marty Robinson: I think it's educating people because, I mean, it's the fear of the unknown. That's the way I always think about it. You just don't know what's coming up.

For example, two weeks ago I was in Guelph and we had a brand new amputee. Young gentleman, 41 years old. This is a traumatic event in his life. And you could tell he was hurting. I had another gentleman who's in his sixties who had been an amputee of the similar level. And I was like, hey, do you mind just talking to this guy even for a few minutes? And, the amount that this guy got out of that connection was huge.

So, I think things like that. I giving people a good guideline and timeline of what, how things are going to go down and that there is hope that the prosthesis can really provide you with a lot, a lot of function and mobility that you've lost. And, yeah, I think it's answering questions, engaging and informing. People want information at that stage. They're lost. A lot of times they haven't been talked to that much in the hospital. I'm surprised at that. So we like to give them little bit of a window to look ahead, a little bit of forward thinking on what's coming up, and that encourages them. They're always surprised to think, oh, I'm going to be walking in two weeks. Yep, we're casting you today and you're going to be up in those parallel bars walking in two weeks. And they're like, oh my God, really? And I'll bring the Kleenex, even for me, 35 years later. The best part is when you get someone going again for the first time. Somehow you share their joy and hard work. We ask people, are you up for this? This is gonna be a lot of hard work, but we're gonna work together and we're gonna get there. So it's encouraging. It's informing. It's a lot of coaching and there's a lot of people who are involved, and I share in their energy and my energy with them, and, man, I get a lot back, too. So, it's fun getting someone going the first time.

[00:29:17] Jeff Tiessen: Oh, I'll bet it is. And that's really cool to hear you say that, that it's not a production line in there. There still is that human connection. And yeah, I would imagine 35 years in the business and working with people, you're learning all the time, let alone about the new technology that is always coming out. So, if you had to think back to when you started and what you know now, is there one thing or a couple of things that you wish you knew when you started in the profession that you know now?

[00:29:52] Marty Robinson: Yeah, that's a good one. That's deep. I think I wasn't aware of how much I could push myself to do more, to get deeper with any problem that might exist, because there is technology, lots of technology available, but it's not even about that. It's about, for me, not being afraid to make the connection. Connection and the commitment. I guess that's what I would say that I learned from when I started out at Chedoke, when I didn't know anything and was motivated and excited about everything, but didn't really know what I could offer and how far I could extend that. But now I guess it's the confidence, knowing my limitations and knowing how far I can push myself to push somebody else.

[00:30:54] Jeff Tiessen: And you mentioned earlier, too, about not over-promising. Yeah?

[00:30:59] Marty Robinson: That's a really big part of it, too, the expectations, like defining things in the beginning when you're starting a new project, a new commitment with somebody, and really being honest. Not everything's positive. I think it's so easy for us to get somebody all pumped up, and then sometimes they're let down because we kind of oversold it. And I think anyone would appreciate the real story and the real picture. And it’s important that they know that a big part of it is their commitment and their energy in the project too. Like, you're going to work hard, and you're going to get a lot out of this. I'm going to do my best for you. The therapist is going to try to really be engaged in helping you learn how to get off the floor and how to do all the different phases of gait and what kind of training and exercises you need to do to prepare for that. But, yeah, I think laying it out in the beginning and being very honest is really important. And you know what I learned too Jeff, is now I take more time in the beginning of starting a project. Before I was in such a rush to get on with it and get going, and I felt that pressure of getting things done, that sometimes I didn't take the time to really figure out where I was going and what was the plan and what are we doing here? Like, get as much information in the first couple of visits with a new client as you possibly can, because once that person leaves your clinic, then you're speculating at that point. Some information is lost. So, yeah, I just take more time in the beginning to really, really, get as much information and as much detail that I need to make decisions on what kind of foot to go with, what type of socket style. Maybe back in the day I wouldn’t have, but when I see the way you live your life, I'm like, that wouldn't have made any sense. But I couldn't have imagined that at the time. It seemed like more is better or more expensive is better. Well, that's not always the case. So, yeah, I think just slowing down the beginning. I worked with a German colleague for a few years when I worked with Ottobock, and he had a great approach. He was never in a hurry to go to the next step until you're completely happy with the step that you're at. And, you know, from having sockets fit and that's usually the check-socket stage, do not go to finishing the socket until you're 100 percent confident that you're there. Do another check socket. Take another fitting. It's not that much.

[00:34:08] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, but you've got us wanting you to rush. We want stuff done quickly.

[00:34:15] Marty Robinson: Yeah, and sometimes we both collectively suffer from that approach because what happens is it could be better. It could have been, you know, a better end result, and it does take time.

[00:34:30] Jeff Tiessen: Do you ever think about what you might be doing if, you know, this prosthetist profession didn't work out for you? Aside from tuck shop work?

[00:34:42] Marty Robinson: i don't know. I like teaching, so I did teach for a while. I taught at Guelph. I taught at the college in prosthetics. I got a lot out of that. I think I would have liked teaching.

But this is special. You know, people ask me, hey, what would you have done if not this. I say, I would have done this. It sounds so cliche, but for me this was the perfect fit. This is a job that I don't have to get psyched up for. I'm 61. I'm not ready to retire. People are asking me about retirement. Sure, I think about retirement but I'm not ready to. I feel like I'm not done yet. I'm still enjoying it, and it's different every day. And it's that challenge. It's the human connection.

There are so many relationships that you establish. It's a pretty intimate type of relationship too. This is different than helping you pick out a pair of jeans. This is way beyond that.

This is part of your self image and your mobility or your function, in your case Jeff. I mean, we know you've got to have three sets of prostheses going at any one time, or it's going to mess up your day, your week, your month, your trip, your whatever, right? So it's very, very important to realize that.

[00:36:22] Jeff Tiessen: I've had a chance to speak at some of your profession’s conferences and I've talked about pulling back the curtains on our lives, as we pull back the curtains on your profession here, but I talk about those couple of hours we spent together a month, and all my other waking hours are dependent on the work that you did in those couple of hours.

[00:36:48] Marty Robinson: Yeah. And I take that seriously. And I think anybody in the profession, if they don't, then they're going to fall short. People say, you got to leave your work at work, and a lot of the new thinking is you work to live, and, well, okay, I get that. But when I'm at work, I take it seriously… the impact of my actions. I've gone to people's homes. I mean, my family would even say to me, why do you do that? I go, I don't know. I just have to; it's just that it's important to me. It's not just about leaving it at work. It's in a pinch. I mean, I can't do it for everybody, but if somebody called me and said, listen, I'm, I'm going to Cuba tomorrow, and my foot's facing north and it should be facing south and I have to take an hour or two hours out, why wouldn't I do that? Okay, I don't want everybody be calling me right now.

It gives me peace. I don't know. It's just something that I've always done, and it's my personal decision. I wouldn't recommend that for everybody. Not everybody's into that, but for me, I always kind of felt like I would be available if really needed.

[00:38:30] Jeff Tiessen: Should we give your phone number right now?

[00:38:32] Marty Robinson: Yeah, sure. But that's the honest truth, though. I've always just been that kind of person. And my parents were like that. And, you know, it's just nice to find a profession where you can satisfy that little part of you, that little cell in there that you get a buzz from going that extra little distance. And there's so many people in this field that are like that. I'm not sure why? Maybe that’s why they got into this.

[00:39:12] Jeff Tiessen: Last one for you. And this is what I'd like to ask everybody who joins me as a guest. So, a great day for you. If that's the recipe, what ingredients go into making for a really good day for you?

[00:39:30] Marty Robinson: Great day. Hmm. Well, we have to keep this PG.

[00:39:38] Jeff Tiessen: Not a bad idea okay.

[00:39:40] Marty Robinson: Well, I love the outdoors. So, a great day for me would be to start by doing something a little bit physical outside. I would love to have my family around on that day. I love having my family close. We do a lot. We still do a lot together.

I don't know. That's a pretty good question, because I'm almost saying I'll get in my car and go to work, but is that bad?

That's why I'm struggling with retirement, because I don't know what I'm going to do. You can only make so many mediocre birdhouses, right? I mean, there's not a huge market for it. It would involve people. I like having people around. I like my private time after work. I get a big fix at work engaging with people. So at some point in the perfect day, I like to engage with people who are close to me.

I like to laugh. I like to make people laugh. I'd like to travel more, a little bit more. So the perfect day would probably be in a different location or a place I've never been to been before. Meet some people that have a different culture.

You and I have been to Belize together. Those kinds of experiences. Well, I think I might have had a perfect day there. Just the feeling of being in a different place where you've helped some people that would normally not have a prosthesis.

[00:41:19] Jeff Tiessen: For context for everyone, that was sort of a working trip, but you were helping some folks in a very poor village that had no access to prosthetic care with not just donated componentry, but your time and your expense and how appreciative they were of that. That's not what we were looking for. It was to help them for sure.

[00:41:46] Marty Robinson: Yeah, I'm appreciative to you for including me in that trip. That's a highlight. One of the highlights of my career actually was doing that.

[00:42:09] Jeff Tiessen: And maybe a home prosthetic visit to someone, to someone's home to help out a little bit?

[00:42:15] Marty Robinson: Well, I swear, if I could have the airstream trailer with the prosthetic clinic in the back and just travel around and still do what I do, because I do love this. I say to some people, hey, this is the only thing I'm good at, right? So, it's Marty's Mobile.

[00:42:37] Jeff Tiessen: I like it.

[00:42:38] Marty Robinson: I get a lot out of it. And that's important to me. There's a lot of satisfaction in the job. A lot of job satisfaction for sure.

[00:42:45] Jeff Tiessen: Wow, what a great place to end. And you've shared so much that I think all of us can kind of just go, hmmm. When it comes to our relationship with prosthetists, orthotists, and how you see it, your perspective. Because like I said, this is kind of pulling back the curtains for us. And when we're in that clinic room and off you go with our limb, we don't know what's going on back there and why it's taking so long.

[00:43:11] Marty Robinson: Don't be afraid to push us because we'll be better for it. And you Jeff, you've made me better because you've challenged me. And, you know I think that it's about honesty. And when you get a good relationship with your prosthetist, I mean, that's a pretty sweet thing because it's like I said, give and take, but we really want to provide as much as we can for you. As far as technology, there's so many great things existing right now that we can offer. But the only thing that hasn't changed is the patience and understanding and listening. Those things will always be important, whether we're getting 3D-printed devices or what have you, or A-I gets involved in some capacity, or osseo-integration which people are investigating. I think that the thing that will always be the same and always will be important is the human element and the connection. For me its what allows me to be a little bit better at my job, for sure.

[00:44:40] Jeff Tiessen: Sounds like that's what you really love about it. So listen, thank you. Thanks for all the insights and really poignant comments. And thank you to all of our listeners. This has been Life and Limb. Again, thanks to Marty Robinson, my prosthetist, and you know, a bit of a legend in the industry, in the profession, no doubt.

Check out previous podcasts and our upcoming guests on our website at thrivemag ca. And you can read about others who are thriving with limb loss or limb difference and plenty more at thrivemag ca, too. Until next time, live well.

Hosted by

Jeff Tiessen, PLY

Double-arm amputee and Paralympic gold-medalist Jeff Tiessen is the founder and publisher of thrive magazine. He's an award-winning writer with over 1,000 published features to his credit. Recognized for his work on and off the athletic track, Jeff is an inductee in the Canadian Disability Hall of Fame. Jeff is a respected educator, advocate and highly sought-after public speaker.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?