Life & Limb - A monthly podcast about Living Well with Limb Loss

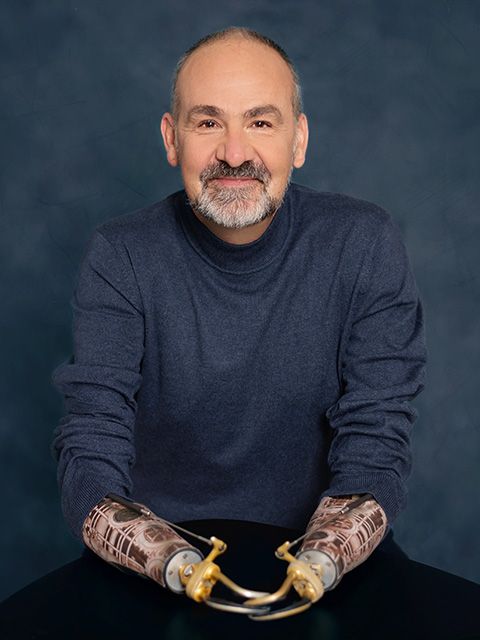

Conquering His Own World – Andrew Haley

Episode Date: November 21, 2024

“You don’t have to conquer the world; you just have to conquer your world,” says Andrew Haley. His is a story of a Halifax kid with a 35 percent chance of survival becoming one of Canada’s most accomplished high-performance athletes. Andrew shares what motivated him from that cancer diagnosis toward four Paralympic Games and five trips to the Paralympic podium.

Episode Transcript

[00:00:03] Jeff Tiessen: Welcome to Life and Limb, a podcast from Thrive magazine, all about living well with limb loss and limb difference. I'm Jeff Tiessen, publisher of Thrive magazine and your podcast host. My guest is a four-time Paralympian from 1992 in Barcelona to 2004 in Athens, and a five-time Paralympic medalist. He's a three-time World Champion, a world record holder, an inductee in the Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame, and a member of Swimming Canada's Circle of Excellence as well. And after his retirement from competitive swimming, he's remained active in the Paralympic movement, sharing his story of a kid with a 35% chance of survival, to becoming one of Canada's most accomplished high performance athletes. Andrew Haley, welcome. Thanks for joining me. And how you doing?

[00:00:52] Andrew Haley: I'm fine, thanks Jeff. Thanks for having me.

[00:00:54] Jeff Tiessen: It's a pleasure. Just a little bit of background. We were teammates and in Barcelona and that's where we got to know each other many, many moons ago. Did you get a chance to watch any of the Paris Games, Paris Paralympics?

[00:01:10] Andrew Haley: Not a lot. I mean, I paid attention specifically to probably wheelchair basketball, both men's and women's. Of course, the swimming caught my eye. The times right now in the pool are way faster than in my day. I can remember back in 2000, our swim team won 26 medals in the pool alone and overall I think we won about 50 odd medals. So, we did quite well as a swim team. But then at Paris, the team won I think in the 20s. 24, 26 medals comes to mind. So, the world has gotten faster. But that's a good thing when you talk about disability and disabled sports because you want other countries competing and vying for medals and you don't want a couple countries, you know, winning all the medals. So, it's really good for the movement that it's evened out a little bit.

[00:02:00] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I was going to ask you about that. It's 20 years since your last Paralympic Games. I know you competed a little bit beyond that, I think, to 2008? And you talk about some of the changes and you still being involved in the Paralympic movement. What other changes have you seen aside from that, that medal count, which, yeah, the world is getting better around us, which is great. But what else, what's different 20 years later?

[00:02:27] Andrew Haley: I think it's just the acceptance overall. You know, back in 1994 when I won Commonwealth Games, the race was live on television across the countries. As far as I know, it was the first time that a disabled athlete was on live television in Canada for disabled events. And then you fast forward to this year in Paris, they had live events streaming online.

Britain and Australia and Brazil are going gangbusters in terms of their coverage for the Paralympics. So, Canada's got a way to go. I mean, we probably sent a couple people over to Paris to do the Games, whereas Britain sent a truckload of people. So, there's some way to go. But at the same time, it has grown so much. The acceptance is there. It could be better.

The idea that the Paralympic gold medals are worth the same as the Olympic gold medal. Still got some work to do there, but it's going in the right direction. And now we have funding for athletes and bonuses for medals. So, you win a gold medal in the Olympics or you win a gold medal in Paralympics, you get the funding the exact same amount. That's a step in the right direction, but we continue on with that, with that journey.

[00:03:53] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, it's a good point. Australia and Britain, maybe Brazil too, they're real sporting nations, aren't they? I mean, even in our time. But there was differentiation between able bodied and para athlete. Would you agree?

[00:04:21] Andrew Haley: Yeah. I mean, back in those ‘92 games you alluded to, I paid $1,000 to represent my country. And during those times Swim Canada was not part of the Paralympic movement in terms of overseeing the para team. And then eventually that took place. But in terms of the other nations, they have just embraced their athletes with praise and with coverage. Britain and Australia, like we mentioned, are very big into that and probably they're leading the charge. The States I can't really comment on because I'm not in the States and see their coverage, but I think that overall there could be a lot more coverage. But it's baby steps and that's okay because we're going somewhere.

[00:05:12] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, yeah. I want to ask you about a little bit of controversy that has surfaced out of the Paralympics. I mean, which is kind of in step with able bodied sport. So. it's kind of a good thing in a weird way. But first, your fondest memory from your sporting career and that may be on the podium, that may be off the podium. What is something that you still remember as a really special moment?

[00:05:43] Andrew Haley: Kind of two moments specifically. One was World Championships in 1998. Only because, like in 1990, I told myself one day I was going to be world champion. And that was not something that somebody from Cape Breton Island with a 25 meter pool, we didn't have a 50 meter pool, normally would say out loud because it just doesn't happen. And then later on in life, then we had Sydney Crosby, Nathan McKinnon, Al McGinnis. Like, there's many athletes that come from my home province that have done really well. So that was great. But also from a Paralympic perspective in 2000, because of what a special team that was. We're talking Benoit Huot, Daniel Campo, Donovan Tilsley. There was so many good athletes on that team that to be able to share a gold medal for the 4 by 100 medley relay with Benoit, Philip Gagnon and Adam Purdy and set a world record and do it on the very last day was super special for me to be able now to call myself a Paralympic champion.

Unfortunately, I didn't do it in an individual race. I was bronze, which is still amazing. But to be able to share it with those guys on the last night was super special and a moment, of course, I'm never going to forget.

[00:06:59] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, interesting you say that. Some of my friends have commented that in watching the Paralympics that there's a sense of camaraderie, of course, within the team, but also extended to other countries. They just sensed it was a bit of a different feel than the Olympics. Do you recall that?

[00:07:20] Andrew Haley: I can't comment specifically on what happens at the Olympics, but I can comment on that. You know, some of my biggest competitors became friends with me. We've kind of lost touch. Michael Pratt from the States, who I competed against, I remember very fondly in 2002 at World Championships. It was between the gold and silver medals - pretty much foregone conclusions. So myself, Brad Sales, a Canadian, and Michael Pratt were competing for the bronze medal. I was lucky enough to be able to win that race, but after the race is over and you get through the emotions of whatever the performance was, you can go into the hall where you eat and you can sit down and talk with that person. And I thought that was really interesting to know people from different sports too.

A guy who was a swimmer In Benoit's classification, S10, gave up swimming and took on track cycling in a velodrome and won a gold medal multiple times. So, you cheer for those people because you see the struggle that some of these athletes have faced. And I think everybody cheers for each other. Obviously, you don't cheer for somebody who's trying to beat you in a particular race, but outside of that, you're cheering for their successes. Because we all know that to be part of the Paralympics requires some level of disability, some level of overcoming obstacles, some level of resilience, some level of positive thought and mindset, which you may not find at the Olympic level. So, you'll find some people will talk about the Paralympics being their favourite Games because of that. They dealt with struggle. They know what a struggle was like. And we're not talking struggle in terms of, you know, trying your sport, but trying a struggle in terms of climbing Mount Everest. Congratulations to those who've done it. But that's a struggle you bring upon yourself as Paralympic athletes. The struggle we have was brought upon us by factors that were not our doing. So, there's a difference there. And I think that, you know, struggle unites.

[00:09:18] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I would agree. I think that commonality, that's the thread that runs through the fabric for us all, and leaning into a bit of the controversy, and it was present with the Paris Paralympics. I'm just kind of interested in your opinion on it, if you have one. It centers around the messaging that the International Paralympic Committee and the Canadian Paralympic Committee too, are putting out around inclusion, and that these Games are now a model of inclusion and a beacon for inclusion beyond the Games themselves. And some of the critics are saying, hey, just stay in your sports lane. And I'm wondering what you think about that. Do you think the Games impact workplace inclusion or community inclusion or whatever it may be out of sport? What is that impact that you see?

[00:10:14] Andrew Haley: Well, excuse me, but how many people actually watch the Games in Canada? We don't know the answer to that question. So, yes, there's inclusion. Yes. CBC. Many different media outlets have taken up the Games in terms of trying to broadcast them to Canadians, and hopefully Canadians watch. We know that there's a significant difference between who watched the Olympics and who watched the Paralympics.

I liked to see that Aurlie Rivard won a gold medal. And to see that on Sportsnet I thought was saying something because they only write stuff typically if it's news. And the fact that they consider that that was news was interesting. Back in my day, winning a medal at the Paralympics back in Nova Scotia apparently wasn't news until I made it news. Things changed. So, there's still a long way to go. I mean people can say that it's, you know, inclusion, diversity. Yes, it is. But it's why they call it a movement. It's going to continue to move on. How are we leading into the next Winter Olympics? How are we leading into LA in 2028? And, how are we supporting our athletes in between Paralympics? So that's the big thing. I mean, we support our athletes in 2020, 2021, for Tokyo. We support our athletes in 2024 for Paris. What about 2026, 2028? Like the support needs to be continuing on. It's getting better. The Paralympic committee led by Karen O'Neill are doing amazing things. She is a terrific advocate and our whole team is terrific advocates for disabled sport in Canada. But we need to continue that momentum. We need to take what we have from the Paralympics and continue on to support the athletes, not just when the lights are on, but when the lights are off. And not to say they're not doing that, but I think as an overall society we need to make sure that athletes are supported.

[00:12:26] Jeff Tiessen: I really like that comment about when the lights are off. And you know, I noticed that on the evening news, Global, CBC, you know, city news that we watch here in southern Ontario. It was a news item that came up. You could track who won medals at the games by watching the evening news. That, that was not in our time, as you said.

[00:12:50] Andrew Haley: And one of the things that really resonated with me a little bit in terms of swimming. I mean, obviously I didn't look at some of the other sports, but it's also about how close races are. So when I take a look at some of the races from years gone by, you know, somebody wins a gold medal, let's say, making this up. 1:18, next place 1:22., next place, 1:24. How excited can you get for a race when there's like 2 seconds between in 100 meter freestyles? It's almost like a complete foregone conclusion who was going to win gold, silver, bronze. That to me is not really sport. Sport is competitive. And we saw the competitiveness in many of the different races at the Paralympics this year. It's not going to be perfect because obviously the lower classifications, in many different sports, you're going to have different levels of ability, especially from the lower classifications. But some of those higher-level classifications, especially in swimming in S9, S10, S13, which is more of a visual category, and 14, which is more of a mental capacity category, it's really competitive. And that's the one thing that I really kind of focused on, is that if you want to have the medals be the same value as the Olympic medals, as Benoit Huot and others have been passionate about, you need the sport to have the credibility to say that was a very competitive field and to the winner, full marks for winning that, because they won that race by a hundredth of a second, a tenth of a second, two tenths of a second. That is where you're going to get the credibility. You need the field to be stronger. And we're getting there.

[00:14:27] Jeff Tiessen: And I think that's attractive to the spectator, right, or the viewer? And then missing a leg below the knee, above the knee, whatever the disability may be, it almost becomes incidental. That was just really good entertainment, I would think. Hey, let's talk about the time in your life when you lost your leg. You've said that you were a very self-conscious kid after losing your leg to cancer and that you covered it up, you didn't wear shorts. You're a very self-confident individual, so what was that pathway for you? How did you get from there to here? And I guess it's kind of an advice question maybe for some, but what brought you to your confidence level now? And of course, sport is an easy answer in that. But start with what age you were when you lost your leg.

[00:15:22] Andrew Haley: Yeah, so I was six when I lost it. I had osteogenic sarcoma, same cancer that Terry Fox had pretty much around the same time, 1980 as well. My hair fell out, hair grew back, which is great. Then had lung cancer. Hair fell out, hair grew back. And the trials and tribulations of being able to, to go through that was extremely difficult. You know, my mom was living in Cape Breton, north of Sydney. So, it's like four hours, four and a bit hours, away from Halifax. The chemotherapy was trying to keep me alive. There's a lot of different kids that were on my floor. You know, we wake up, the next morning, and they passed away. So, it was a difficult time to go through before advances in modern medicine these days. I'm told that if I had the same cancer, I may not have lost my leg. But I’m extremely happy to be living. Then, you know, eventually getting fitted for a prosthetic leg and having to walk on that and going through growth spurts as a child and getting a new leg made. It was just a lot, you know, it was a lot to go through. In terms of the question about my shorts and then not covering up my leg. I mean, certainly right now I still wear shorts past the knee, but I'm not as self-conscious as I used to be because the Paralympics really brought out the disabled person inside of me and gave me a lot more self-confidence than I had before.

I didn't want people to see me without my artificial leg on. But when I was in the pool, I didn't care. You know, I'm competing against seven other competitors in the pool on national television, and I didn't care because I was so focused on the race and what I was doing. When you go to the Paralympics, as you know, and you're able to walk around with shorts on and T shirts on, if you're an arm amp or whatever, and you don't need to cover up that, that's empowering because there are other people generally in my situation or worse off than I was. So, like, why am I feeling sorry for myself when I know somebody's out there who's a paraplegic, quadriplegic, blind, so on and so forth? So, it really kind of put it in perspective. And I was starting to get success. I had early success.

World championships were 1990. By 1992, I'd won my first Paralympic bronze medal. 94, I'm winning Commonwealth Games, multiple medals at World Championships, and just kept going on and on. So, the advice out there for people who have a prosthetic leg or have a prosthetic arm, who are watching this is… I'm going to take you back to something I do sometimes in my motivational speaking around what's not at stake. What’s not at stake in terms of, what you're doing in your life. If you wore shorts and people saw your leg or people saw your arm, you're still going to have parents who are going to love you. You're still going to have siblings, if you have them, who are going to support you. You still have friends who are going to support you. Workers at work are going to support you. Your dog or your cat is going to come, probably say hello when you walk in the front door. These are all things that no matter what happens in your career, whatever, these are the rocks. These are the things that are not at stake. Having that mentality saying well, what happens if I wear shorts today? Well, people look at me differently maybe. Do I care? Maybe not so much as I used to because I'm trying to be very comfortable in my own body, in what I have to offer. And that just is a gradual progression. It's not going to be easy. But if you have support of others around you, it's, it certainly makes the journey a lot easier.

[00:19:08] Jeff Tiessen: That's really powerful. And then that's outside of sport. I like the way you finished that with that empowerment. And it reminds me of something I read or heard you say about this, and this is a quote from you. You don't have to conquer the world, you just have to conquer your world. How did you come to understand that? I know your mom was quite influential. Influential in your life, in your recovery, but yeah, where'd that come from?

[00:19:35] Andrew Haley: Yeah, both my mom and dad. My mom took my hand and said, Andrew, it doesn't matter how many times you get knocked down. It matters how many times that you get up, that determines the quality of your life.

And the whole idea about you don't have to conquer the world, you have to conquer your world. Because when we are dealing with a loss, the whole world could conspire against you. It's kind of a lesson that you learn when you're in sport. Just focus on what you need, what you can focus on. Like, don't focus on things that are outside your control. So, the whole idea about conquering the world is that, just make sure that you are just present in the moment. You know, don't get locked in the past, don't get, you know, barefoot, flat-footed, looking at the future. Look at the present, look at what you're doing in the present. And that will be where you need to go.

[00:20:35] Jeff Tiessen: I want to talk to you more about some of that messaging that you share in your public speaking. And we're going to wrap up with that. But I want to come around to you being a dad with a disability. And from my experience, I remember when I was a dad waiting on the first child, there really were some anxious moments as I was conjuring and envisioning what parenting challenges would be related to my disability. And I've heard the same from friends with vision loss or friends who use wheelchairs. Did you experience any of that contemplation or reservation when you were waiting for your kids to be born as an above-knee amputee to be a dad?

[00:21:21] Andrew Haley: Yeah, a couple times. I mean, I think that the first thought was, can I be a dad because of my disability. Not because of my disability, but because of the chemotherapy that I had because of my genetic makeup. And I’ve got two great kids. So that was put to bed. But also, when my daughter was 6, she's 13 now, but when she was 6, it really hit home for me because seeing other kids out there who are 6, 7, 8 years old, the same age I was when I had cancer. I got into enough schools to talk to elementary school kids to see enough 6 year olds in my life. But to see my daughter being six, that was difficult. And then eight. Let's get you through six to eight. Right? Let's get you through that time. But then when I had my son, he's eight now, that was a different scenario for me because the situation was he's a boy, I was a boy. And that was a dip. That was a little bit different for me because now we're talking about a boy child and will he be able to make it through. So that was unique. But by far and large, you know, the kids don't care that I have one leg. My daughter actually has heard my speech because I'm practicing at home more times than she can probably count. And then sometimes she jokes around with different parts of it because she knows it so well. So overall the kids are supportive. They don't see the disability. My wife doesn't see the disability, which is fantastic and kudos to all the people out there who are involved, partner, spouse, whatever, with somebody with disability. And you've overlooked that component and you saw the true person inside. Because I think sometimes there are people out there with a disability who really have an apprehension about dating, about showing their disability to that partner before they even know. Right? So how does that work out? How does it work out where if you say, hey, by the way, I have a disability.

I know that already. It's a tricky time. Let's say you're on a dating app and you're like, do you share it? Like how does it work? Like, you say I have a disability right away or you get to know the person, then say it. So, it's a challenge. That whole idea, how did you manage it?

[00:23:48] Jeff Tiessen: How did you manage that? What you're talking about with your wife, did you, let's call it disclose? That's kind of a harsh word. But when she met you, did she know you were an amputee?

[00:24:02] Andrew Haley: Well, the funny part was I actually met her – her name is Renata - at the Paralympics. Sorry, I mean at the Parapans in 2007 in Rio. She was part of the medal ceremony group. I had won three medals so I got chit chatting with her. Medal number one, medal number two, medal number three. And when I left the village that particular day she actually happened to be there trading her jacket with another one of my teammates. And I didn't anticipate ever seeing her again. One of my teammates had her contact information. I wanted to go back to Rio because I wanted to basically view the city. We kept in touch and here we are 16 plus years later. So, I didn't really have to share it too much because I was at a Parapan Games where they know about disability. So, it was kind of easy to a certain extent. I didn't have to face that, that component. But there have been times where I've dated people where I have had to face it.

[00:25:01] Jeff Tiessen: That's an interesting story. Something you got more than just five medals out of, out of the Paralympic Games. You got a bride as well.

[00:25:10] Andrew Haley: Yeah, I mean, ultimately the five medals are great. Obviously, I happy with the way it turned out from a personal perspective, but also from a perspective of the benefits of the self esteem, of the confidence, of the friendships, of the travel and the experiences to be able to go somewhere and say I came here for sport, like Australia. If I was ever back to Australia, I will instantly recognize my accomplishments because Sydney Olympic Park has our medal ingrained in a Plaque on site. And so that would be nice to go back and see it one day. A friend of mine went to Australia many years ago and saw it and took a photo of it because I had no idea that it was there and sent it back to me. So, there's just many different things that sport, as you know, bring to us. But I want to be very clear with the people who are listening to this that have just experienced some sort of limb loss and just experienced their life being potentially upside down. You know, we're spending a lot of time talking about sports and how amazing sports is, and I thoroughly encourage anybody here to participate in sports if you can afford it and if there's means to be able to get around that through Paralympic and otherwise, but also just to have the knowledge that you're not alone in your journey. You know, the reason that Jeff and myself are here today to talk about this is because we feel that, as old dogs if you will, that there's a reason that we want to give back to you, the listener, to know that you're not alone in your journey. You're not alone. Know full well that we as people who have been through it, still have our challenges, still have days when we don't want to get out of bed, still have days when life seems insurmountable, but we have the wherewithal and the experience to know that we can persevere and overcome challenges and obstacles in our way. And I want to fire that back to everybody listening that you too can have that superhuman power inside of you. You just have to rely on others and know that tomorrow the sun will come up for you somewhere and to be strong and go after what you believe in. Know that some people will judge you, but your friends will never judge you. And that's what you have to hold on to.

[00:27:38] Jeff Tiessen: You are so right, Andrew. That is so, so powerful and you know, a message for us, our community, because I know a lot of your messaging is using experiences and anecdotes and you know that lived experience, and you share that generally with able bodied audiences, for lack of a better word, when you're on the corporate stage. After you retired from sport, you had a 14-year-career with the Toronto Blue Jays. Not on the field, but behind the scenes, working in ticketing, I think it was. Right?

[00:28:13] Andrew Haley: That's right, yeah.

[00:28:14] Jeff Tiessen: And then from there, and particularly now, you're working to get back into public speaking, which you are exceptional at. So, what's the motivation for getting back onto the stage? And what's the message for those audiences?

[00:28:31] Andrew Haley: I'm presuming mostly corporate, corporate conferences, events. So, the motivation is because I think in the travels that I've been through, people need motivation more than ever. You know, the pandemic left a mark. I think people generally need some level of pick me up in terms of their daily life.

The message that I try to impart on my audiences is all about a gold medal moment. And that gold medal moment does not have to necessarily be winning a gold medal. When I won the bronze medal in 1992 at the Paralympics in the 400 freestyle, that felt like a gold medal because that was higher than everything that I thought possible. But in some cases, your Paralympic or your gold medal moment may be 20th, maybe 10th, and that's okay. It doesn't actually have to win the medal. So I tell the audience to go after what they can control and go after whatever their dreams are, and to surround themselves with a great team, a positive attitude, and make sure that they know that they can do anything they want in life and being able to give them tangible techniques and skills that they can go and challenge the world with. Somebody once said to me, Andrew, you've sacrificed so much in your career to accomplish what you've accomplished. And my response back was, I've never sacrificed anything in my career. I've invested my time to be the best I possibly can be every single time. So, it's just a mind shift from the negative of I sacrificed, because I didn't sacrifice, and I continued on doing what I was doing.

[00:30:23] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I've used that same language too. And I agree with you. I mean, we made choices and yeah, there were things we missed out on. And maybe we weren't always the best brother or sister or friend when we were dedicated to competing, but absolutely we were invested in us for the rewards that came with that. You said something about control, and I want to finish up on that because I certainly related to what you were talking about in one of your presentations that I was watching. And it's something that I learned through track. Would I have learned it elsewhere? Probably. I learned that the only person you can control is, yourself. And I remember being on the starting line nervous, anxiously looking at the German athlete to one side, the Polish athlete to the other, the Chinese athlete and wondering how they were going to do that day. But that's irrelevant. It was all about what I could control and what I could do that day. And you've talked about controlling the controllable. So let's use that as a launch platform here for advice back to our community of amputees, those who are just starting on the journey. Maybe kids, maybe seniors, or those who’ve been down that path for a while. Package it for me, Andrew, that control the controllable.

[00:31:43] Andrew Haley: I'll give you a little bit of a story. Back in the early 90s, I just started swimming. I went to a competition in Anagonish, Nova Scotia, and I swam a race. It was 100 meter freestyle. I knew that because I was a disabled athlete that I wanted to beat one athlete. That's all I wanted to do. His name was Timmy. And what happened was I looked at the scoreboard at the end of the race and Timmy beat me. I finished last and I hopped over to where I was sitting and my coach came over and said, how did that go? And I'm like, well, you saw I was last. I lost. And I was defiant. I was dejected. And he goes, well, I don't actually see it that way. And I was getting irritated because I'm like, it was the fact I lost. And he said to me, what was your best time? I said, well, my best time was 1 minute and 20 seconds. He said, what did you go? I said, 1 minute and 18 seconds. He said, you know what you did? I was like, well, what did I do? He said, you just set a personal world record. And there's a difference there in terms of world records. When I see personal world records, essentially is the best time.

He said, but what happened was is that going into this race you were only focused on Timmy. You weren't focused on your starts, you weren't focused on your turn, you weren't focused on your propulsion, you weren't focused on what you could control. You were too worried about what he was going to go. So, I could have gone to best time, but because I didn't beat him, I considered that a failure. He said, you need to start controlling what you can control. I started realizing that I had the power to control my own body ship, let's call it. Not only did I beat Timmy, I beat a lot of other people because I blocked out the things that were going to conspire against me. I just focused on what I knew that I could handle, and I made things happen. So, my advice to the people listening is to really put aside the doubts, really put aside what you cannot control.

I cannot control the fact I lost my leg. I can complain about it. It's not going to help. So, I have to move past that. You can't complain that unfortunately you're a paraplegic, a quadriplegic, lost your arm, lost your leg, something else happened. You can't. You can complain about it, and somebody might listen, but it's not really going to get you too far. So, you have to deal with it and you have to embrace it the best you possibly can. Embrace that situation. I'm reminded a little bit by, I can't remember his name, I think it's Jacob, but I could be wrong. The individual athlete who was part of the Humbolt Broncos, the goaltender who was paralyzed because of the terrific accident many years ago, and now he competes for Canada in para rowing. He just competed in Paris Paralympics. And amazing how the mindset to put the disability aside and make the best of what is a horrible situation. I've done it, Jeff. You've done it. He's done it. Many have done it. That's why you were in the Paralympics. So, if you need support, go to your local area to get the support from family, from friends, from a sport organization.

And things are a lot better, a lot better than my day. And look what I did. You know, we've gone through my results. So good luck to everybody watching and listening because I think there's some positive moments that you want to do. And the other thing I want to leave with is, consider your life a book. It's going to be written regardless of what you do. Because it's going to be written in regards to what you do. If somebody's to read that book in five years and 10 years, would you not want them to read good things about you? I would. That's why I try to do good things with my kids and what I'm doing. So, make sure that you're always going out there with the best foot forward and the best job you can put forward. So that book that is being written by AI or whatever, again, this is all fictional, is being the best version of yourself without excuses, without whining. Maybe a little, but basically being as positive you can be to move yourself forward with the support around you, which I'm sure is just a matter of asking.

[00:36:16] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, so well said, Andrew. Coming from a Paralympic champion with huge dreams and goals and aspirations and accomplishments, you know, you've kind of boiled the ocean down to small victories and one step at a time and small achievements and appreciating those. Right? And that's important too.

Thank you so much for the time this morning. And if you want to learn more about Andrew, plenty to learn. And you can see some of his clips from his presentations at Andrew Haley.ca. Again, thank you so much.

[00:36:59] Andrew Haley: A lot of fun anytime and good luck everybody.

[00:37:02] Jeff Tiessen: This has been Life and Limb. Thank you all for listening. You can read about others who are thriving with limb loss or limb difference and plenty more at Thrivemag.ca. And you'll find our previous podcast episodes there too. Until next time Live Well.

[00:00:52] Andrew Haley: I'm fine, thanks Jeff. Thanks for having me.

[00:00:54] Jeff Tiessen: It's a pleasure. Just a little bit of background. We were teammates and in Barcelona and that's where we got to know each other many, many moons ago. Did you get a chance to watch any of the Paris Games, Paris Paralympics?

[00:01:10] Andrew Haley: Not a lot. I mean, I paid attention specifically to probably wheelchair basketball, both men's and women's. Of course, the swimming caught my eye. The times right now in the pool are way faster than in my day. I can remember back in 2000, our swim team won 26 medals in the pool alone and overall I think we won about 50 odd medals. So, we did quite well as a swim team. But then at Paris, the team won I think in the 20s. 24, 26 medals comes to mind. So, the world has gotten faster. But that's a good thing when you talk about disability and disabled sports because you want other countries competing and vying for medals and you don't want a couple countries, you know, winning all the medals. So, it's really good for the movement that it's evened out a little bit.

[00:02:00] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I was going to ask you about that. It's 20 years since your last Paralympic Games. I know you competed a little bit beyond that, I think, to 2008? And you talk about some of the changes and you still being involved in the Paralympic movement. What other changes have you seen aside from that, that medal count, which, yeah, the world is getting better around us, which is great. But what else, what's different 20 years later?

[00:02:27] Andrew Haley: I think it's just the acceptance overall. You know, back in 1994 when I won Commonwealth Games, the race was live on television across the countries. As far as I know, it was the first time that a disabled athlete was on live television in Canada for disabled events. And then you fast forward to this year in Paris, they had live events streaming online.

Britain and Australia and Brazil are going gangbusters in terms of their coverage for the Paralympics. So, Canada's got a way to go. I mean, we probably sent a couple people over to Paris to do the Games, whereas Britain sent a truckload of people. So, there's some way to go. But at the same time, it has grown so much. The acceptance is there. It could be better.

The idea that the Paralympic gold medals are worth the same as the Olympic gold medal. Still got some work to do there, but it's going in the right direction. And now we have funding for athletes and bonuses for medals. So, you win a gold medal in the Olympics or you win a gold medal in Paralympics, you get the funding the exact same amount. That's a step in the right direction, but we continue on with that, with that journey.

[00:03:53] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, it's a good point. Australia and Britain, maybe Brazil too, they're real sporting nations, aren't they? I mean, even in our time. But there was differentiation between able bodied and para athlete. Would you agree?

[00:04:21] Andrew Haley: Yeah. I mean, back in those ‘92 games you alluded to, I paid $1,000 to represent my country. And during those times Swim Canada was not part of the Paralympic movement in terms of overseeing the para team. And then eventually that took place. But in terms of the other nations, they have just embraced their athletes with praise and with coverage. Britain and Australia, like we mentioned, are very big into that and probably they're leading the charge. The States I can't really comment on because I'm not in the States and see their coverage, but I think that overall there could be a lot more coverage. But it's baby steps and that's okay because we're going somewhere.

[00:05:12] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, yeah. I want to ask you about a little bit of controversy that has surfaced out of the Paralympics. I mean, which is kind of in step with able bodied sport. So. it's kind of a good thing in a weird way. But first, your fondest memory from your sporting career and that may be on the podium, that may be off the podium. What is something that you still remember as a really special moment?

[00:05:43] Andrew Haley: Kind of two moments specifically. One was World Championships in 1998. Only because, like in 1990, I told myself one day I was going to be world champion. And that was not something that somebody from Cape Breton Island with a 25 meter pool, we didn't have a 50 meter pool, normally would say out loud because it just doesn't happen. And then later on in life, then we had Sydney Crosby, Nathan McKinnon, Al McGinnis. Like, there's many athletes that come from my home province that have done really well. So that was great. But also from a Paralympic perspective in 2000, because of what a special team that was. We're talking Benoit Huot, Daniel Campo, Donovan Tilsley. There was so many good athletes on that team that to be able to share a gold medal for the 4 by 100 medley relay with Benoit, Philip Gagnon and Adam Purdy and set a world record and do it on the very last day was super special for me to be able now to call myself a Paralympic champion.

Unfortunately, I didn't do it in an individual race. I was bronze, which is still amazing. But to be able to share it with those guys on the last night was super special and a moment, of course, I'm never going to forget.

[00:06:59] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, interesting you say that. Some of my friends have commented that in watching the Paralympics that there's a sense of camaraderie, of course, within the team, but also extended to other countries. They just sensed it was a bit of a different feel than the Olympics. Do you recall that?

[00:07:20] Andrew Haley: I can't comment specifically on what happens at the Olympics, but I can comment on that. You know, some of my biggest competitors became friends with me. We've kind of lost touch. Michael Pratt from the States, who I competed against, I remember very fondly in 2002 at World Championships. It was between the gold and silver medals - pretty much foregone conclusions. So myself, Brad Sales, a Canadian, and Michael Pratt were competing for the bronze medal. I was lucky enough to be able to win that race, but after the race is over and you get through the emotions of whatever the performance was, you can go into the hall where you eat and you can sit down and talk with that person. And I thought that was really interesting to know people from different sports too.

A guy who was a swimmer In Benoit's classification, S10, gave up swimming and took on track cycling in a velodrome and won a gold medal multiple times. So, you cheer for those people because you see the struggle that some of these athletes have faced. And I think everybody cheers for each other. Obviously, you don't cheer for somebody who's trying to beat you in a particular race, but outside of that, you're cheering for their successes. Because we all know that to be part of the Paralympics requires some level of disability, some level of overcoming obstacles, some level of resilience, some level of positive thought and mindset, which you may not find at the Olympic level. So, you'll find some people will talk about the Paralympics being their favourite Games because of that. They dealt with struggle. They know what a struggle was like. And we're not talking struggle in terms of, you know, trying your sport, but trying a struggle in terms of climbing Mount Everest. Congratulations to those who've done it. But that's a struggle you bring upon yourself as Paralympic athletes. The struggle we have was brought upon us by factors that were not our doing. So, there's a difference there. And I think that, you know, struggle unites.

[00:09:18] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I would agree. I think that commonality, that's the thread that runs through the fabric for us all, and leaning into a bit of the controversy, and it was present with the Paris Paralympics. I'm just kind of interested in your opinion on it, if you have one. It centers around the messaging that the International Paralympic Committee and the Canadian Paralympic Committee too, are putting out around inclusion, and that these Games are now a model of inclusion and a beacon for inclusion beyond the Games themselves. And some of the critics are saying, hey, just stay in your sports lane. And I'm wondering what you think about that. Do you think the Games impact workplace inclusion or community inclusion or whatever it may be out of sport? What is that impact that you see?

[00:10:14] Andrew Haley: Well, excuse me, but how many people actually watch the Games in Canada? We don't know the answer to that question. So, yes, there's inclusion. Yes. CBC. Many different media outlets have taken up the Games in terms of trying to broadcast them to Canadians, and hopefully Canadians watch. We know that there's a significant difference between who watched the Olympics and who watched the Paralympics.

I liked to see that Aurlie Rivard won a gold medal. And to see that on Sportsnet I thought was saying something because they only write stuff typically if it's news. And the fact that they consider that that was news was interesting. Back in my day, winning a medal at the Paralympics back in Nova Scotia apparently wasn't news until I made it news. Things changed. So, there's still a long way to go. I mean people can say that it's, you know, inclusion, diversity. Yes, it is. But it's why they call it a movement. It's going to continue to move on. How are we leading into the next Winter Olympics? How are we leading into LA in 2028? And, how are we supporting our athletes in between Paralympics? So that's the big thing. I mean, we support our athletes in 2020, 2021, for Tokyo. We support our athletes in 2024 for Paris. What about 2026, 2028? Like the support needs to be continuing on. It's getting better. The Paralympic committee led by Karen O'Neill are doing amazing things. She is a terrific advocate and our whole team is terrific advocates for disabled sport in Canada. But we need to continue that momentum. We need to take what we have from the Paralympics and continue on to support the athletes, not just when the lights are on, but when the lights are off. And not to say they're not doing that, but I think as an overall society we need to make sure that athletes are supported.

[00:12:26] Jeff Tiessen: I really like that comment about when the lights are off. And you know, I noticed that on the evening news, Global, CBC, you know, city news that we watch here in southern Ontario. It was a news item that came up. You could track who won medals at the games by watching the evening news. That, that was not in our time, as you said.

[00:12:50] Andrew Haley: And one of the things that really resonated with me a little bit in terms of swimming. I mean, obviously I didn't look at some of the other sports, but it's also about how close races are. So when I take a look at some of the races from years gone by, you know, somebody wins a gold medal, let's say, making this up. 1:18, next place 1:22., next place, 1:24. How excited can you get for a race when there's like 2 seconds between in 100 meter freestyles? It's almost like a complete foregone conclusion who was going to win gold, silver, bronze. That to me is not really sport. Sport is competitive. And we saw the competitiveness in many of the different races at the Paralympics this year. It's not going to be perfect because obviously the lower classifications, in many different sports, you're going to have different levels of ability, especially from the lower classifications. But some of those higher-level classifications, especially in swimming in S9, S10, S13, which is more of a visual category, and 14, which is more of a mental capacity category, it's really competitive. And that's the one thing that I really kind of focused on, is that if you want to have the medals be the same value as the Olympic medals, as Benoit Huot and others have been passionate about, you need the sport to have the credibility to say that was a very competitive field and to the winner, full marks for winning that, because they won that race by a hundredth of a second, a tenth of a second, two tenths of a second. That is where you're going to get the credibility. You need the field to be stronger. And we're getting there.

[00:14:27] Jeff Tiessen: And I think that's attractive to the spectator, right, or the viewer? And then missing a leg below the knee, above the knee, whatever the disability may be, it almost becomes incidental. That was just really good entertainment, I would think. Hey, let's talk about the time in your life when you lost your leg. You've said that you were a very self-conscious kid after losing your leg to cancer and that you covered it up, you didn't wear shorts. You're a very self-confident individual, so what was that pathway for you? How did you get from there to here? And I guess it's kind of an advice question maybe for some, but what brought you to your confidence level now? And of course, sport is an easy answer in that. But start with what age you were when you lost your leg.

[00:15:22] Andrew Haley: Yeah, so I was six when I lost it. I had osteogenic sarcoma, same cancer that Terry Fox had pretty much around the same time, 1980 as well. My hair fell out, hair grew back, which is great. Then had lung cancer. Hair fell out, hair grew back. And the trials and tribulations of being able to, to go through that was extremely difficult. You know, my mom was living in Cape Breton, north of Sydney. So, it's like four hours, four and a bit hours, away from Halifax. The chemotherapy was trying to keep me alive. There's a lot of different kids that were on my floor. You know, we wake up, the next morning, and they passed away. So, it was a difficult time to go through before advances in modern medicine these days. I'm told that if I had the same cancer, I may not have lost my leg. But I’m extremely happy to be living. Then, you know, eventually getting fitted for a prosthetic leg and having to walk on that and going through growth spurts as a child and getting a new leg made. It was just a lot, you know, it was a lot to go through. In terms of the question about my shorts and then not covering up my leg. I mean, certainly right now I still wear shorts past the knee, but I'm not as self-conscious as I used to be because the Paralympics really brought out the disabled person inside of me and gave me a lot more self-confidence than I had before.

I didn't want people to see me without my artificial leg on. But when I was in the pool, I didn't care. You know, I'm competing against seven other competitors in the pool on national television, and I didn't care because I was so focused on the race and what I was doing. When you go to the Paralympics, as you know, and you're able to walk around with shorts on and T shirts on, if you're an arm amp or whatever, and you don't need to cover up that, that's empowering because there are other people generally in my situation or worse off than I was. So, like, why am I feeling sorry for myself when I know somebody's out there who's a paraplegic, quadriplegic, blind, so on and so forth? So, it really kind of put it in perspective. And I was starting to get success. I had early success.

World championships were 1990. By 1992, I'd won my first Paralympic bronze medal. 94, I'm winning Commonwealth Games, multiple medals at World Championships, and just kept going on and on. So, the advice out there for people who have a prosthetic leg or have a prosthetic arm, who are watching this is… I'm going to take you back to something I do sometimes in my motivational speaking around what's not at stake. What’s not at stake in terms of, what you're doing in your life. If you wore shorts and people saw your leg or people saw your arm, you're still going to have parents who are going to love you. You're still going to have siblings, if you have them, who are going to support you. You still have friends who are going to support you. Workers at work are going to support you. Your dog or your cat is going to come, probably say hello when you walk in the front door. These are all things that no matter what happens in your career, whatever, these are the rocks. These are the things that are not at stake. Having that mentality saying well, what happens if I wear shorts today? Well, people look at me differently maybe. Do I care? Maybe not so much as I used to because I'm trying to be very comfortable in my own body, in what I have to offer. And that just is a gradual progression. It's not going to be easy. But if you have support of others around you, it's, it certainly makes the journey a lot easier.

[00:19:08] Jeff Tiessen: That's really powerful. And then that's outside of sport. I like the way you finished that with that empowerment. And it reminds me of something I read or heard you say about this, and this is a quote from you. You don't have to conquer the world, you just have to conquer your world. How did you come to understand that? I know your mom was quite influential. Influential in your life, in your recovery, but yeah, where'd that come from?

[00:19:35] Andrew Haley: Yeah, both my mom and dad. My mom took my hand and said, Andrew, it doesn't matter how many times you get knocked down. It matters how many times that you get up, that determines the quality of your life.

And the whole idea about you don't have to conquer the world, you have to conquer your world. Because when we are dealing with a loss, the whole world could conspire against you. It's kind of a lesson that you learn when you're in sport. Just focus on what you need, what you can focus on. Like, don't focus on things that are outside your control. So, the whole idea about conquering the world is that, just make sure that you are just present in the moment. You know, don't get locked in the past, don't get, you know, barefoot, flat-footed, looking at the future. Look at the present, look at what you're doing in the present. And that will be where you need to go.

[00:20:35] Jeff Tiessen: I want to talk to you more about some of that messaging that you share in your public speaking. And we're going to wrap up with that. But I want to come around to you being a dad with a disability. And from my experience, I remember when I was a dad waiting on the first child, there really were some anxious moments as I was conjuring and envisioning what parenting challenges would be related to my disability. And I've heard the same from friends with vision loss or friends who use wheelchairs. Did you experience any of that contemplation or reservation when you were waiting for your kids to be born as an above-knee amputee to be a dad?

[00:21:21] Andrew Haley: Yeah, a couple times. I mean, I think that the first thought was, can I be a dad because of my disability. Not because of my disability, but because of the chemotherapy that I had because of my genetic makeup. And I’ve got two great kids. So that was put to bed. But also, when my daughter was 6, she's 13 now, but when she was 6, it really hit home for me because seeing other kids out there who are 6, 7, 8 years old, the same age I was when I had cancer. I got into enough schools to talk to elementary school kids to see enough 6 year olds in my life. But to see my daughter being six, that was difficult. And then eight. Let's get you through six to eight. Right? Let's get you through that time. But then when I had my son, he's eight now, that was a different scenario for me because the situation was he's a boy, I was a boy. And that was a dip. That was a little bit different for me because now we're talking about a boy child and will he be able to make it through. So that was unique. But by far and large, you know, the kids don't care that I have one leg. My daughter actually has heard my speech because I'm practicing at home more times than she can probably count. And then sometimes she jokes around with different parts of it because she knows it so well. So overall the kids are supportive. They don't see the disability. My wife doesn't see the disability, which is fantastic and kudos to all the people out there who are involved, partner, spouse, whatever, with somebody with disability. And you've overlooked that component and you saw the true person inside. Because I think sometimes there are people out there with a disability who really have an apprehension about dating, about showing their disability to that partner before they even know. Right? So how does that work out? How does it work out where if you say, hey, by the way, I have a disability.

I know that already. It's a tricky time. Let's say you're on a dating app and you're like, do you share it? Like how does it work? Like, you say I have a disability right away or you get to know the person, then say it. So, it's a challenge. That whole idea, how did you manage it?

[00:23:48] Jeff Tiessen: How did you manage that? What you're talking about with your wife, did you, let's call it disclose? That's kind of a harsh word. But when she met you, did she know you were an amputee?

[00:24:02] Andrew Haley: Well, the funny part was I actually met her – her name is Renata - at the Paralympics. Sorry, I mean at the Parapans in 2007 in Rio. She was part of the medal ceremony group. I had won three medals so I got chit chatting with her. Medal number one, medal number two, medal number three. And when I left the village that particular day she actually happened to be there trading her jacket with another one of my teammates. And I didn't anticipate ever seeing her again. One of my teammates had her contact information. I wanted to go back to Rio because I wanted to basically view the city. We kept in touch and here we are 16 plus years later. So, I didn't really have to share it too much because I was at a Parapan Games where they know about disability. So, it was kind of easy to a certain extent. I didn't have to face that, that component. But there have been times where I've dated people where I have had to face it.

[00:25:01] Jeff Tiessen: That's an interesting story. Something you got more than just five medals out of, out of the Paralympic Games. You got a bride as well.

[00:25:10] Andrew Haley: Yeah, I mean, ultimately the five medals are great. Obviously, I happy with the way it turned out from a personal perspective, but also from a perspective of the benefits of the self esteem, of the confidence, of the friendships, of the travel and the experiences to be able to go somewhere and say I came here for sport, like Australia. If I was ever back to Australia, I will instantly recognize my accomplishments because Sydney Olympic Park has our medal ingrained in a Plaque on site. And so that would be nice to go back and see it one day. A friend of mine went to Australia many years ago and saw it and took a photo of it because I had no idea that it was there and sent it back to me. So, there's just many different things that sport, as you know, bring to us. But I want to be very clear with the people who are listening to this that have just experienced some sort of limb loss and just experienced their life being potentially upside down. You know, we're spending a lot of time talking about sports and how amazing sports is, and I thoroughly encourage anybody here to participate in sports if you can afford it and if there's means to be able to get around that through Paralympic and otherwise, but also just to have the knowledge that you're not alone in your journey. You know, the reason that Jeff and myself are here today to talk about this is because we feel that, as old dogs if you will, that there's a reason that we want to give back to you, the listener, to know that you're not alone in your journey. You're not alone. Know full well that we as people who have been through it, still have our challenges, still have days when we don't want to get out of bed, still have days when life seems insurmountable, but we have the wherewithal and the experience to know that we can persevere and overcome challenges and obstacles in our way. And I want to fire that back to everybody listening that you too can have that superhuman power inside of you. You just have to rely on others and know that tomorrow the sun will come up for you somewhere and to be strong and go after what you believe in. Know that some people will judge you, but your friends will never judge you. And that's what you have to hold on to.

[00:27:38] Jeff Tiessen: You are so right, Andrew. That is so, so powerful and you know, a message for us, our community, because I know a lot of your messaging is using experiences and anecdotes and you know that lived experience, and you share that generally with able bodied audiences, for lack of a better word, when you're on the corporate stage. After you retired from sport, you had a 14-year-career with the Toronto Blue Jays. Not on the field, but behind the scenes, working in ticketing, I think it was. Right?

[00:28:13] Andrew Haley: That's right, yeah.

[00:28:14] Jeff Tiessen: And then from there, and particularly now, you're working to get back into public speaking, which you are exceptional at. So, what's the motivation for getting back onto the stage? And what's the message for those audiences?

[00:28:31] Andrew Haley: I'm presuming mostly corporate, corporate conferences, events. So, the motivation is because I think in the travels that I've been through, people need motivation more than ever. You know, the pandemic left a mark. I think people generally need some level of pick me up in terms of their daily life.

The message that I try to impart on my audiences is all about a gold medal moment. And that gold medal moment does not have to necessarily be winning a gold medal. When I won the bronze medal in 1992 at the Paralympics in the 400 freestyle, that felt like a gold medal because that was higher than everything that I thought possible. But in some cases, your Paralympic or your gold medal moment may be 20th, maybe 10th, and that's okay. It doesn't actually have to win the medal. So I tell the audience to go after what they can control and go after whatever their dreams are, and to surround themselves with a great team, a positive attitude, and make sure that they know that they can do anything they want in life and being able to give them tangible techniques and skills that they can go and challenge the world with. Somebody once said to me, Andrew, you've sacrificed so much in your career to accomplish what you've accomplished. And my response back was, I've never sacrificed anything in my career. I've invested my time to be the best I possibly can be every single time. So, it's just a mind shift from the negative of I sacrificed, because I didn't sacrifice, and I continued on doing what I was doing.

[00:30:23] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, I've used that same language too. And I agree with you. I mean, we made choices and yeah, there were things we missed out on. And maybe we weren't always the best brother or sister or friend when we were dedicated to competing, but absolutely we were invested in us for the rewards that came with that. You said something about control, and I want to finish up on that because I certainly related to what you were talking about in one of your presentations that I was watching. And it's something that I learned through track. Would I have learned it elsewhere? Probably. I learned that the only person you can control is, yourself. And I remember being on the starting line nervous, anxiously looking at the German athlete to one side, the Polish athlete to the other, the Chinese athlete and wondering how they were going to do that day. But that's irrelevant. It was all about what I could control and what I could do that day. And you've talked about controlling the controllable. So let's use that as a launch platform here for advice back to our community of amputees, those who are just starting on the journey. Maybe kids, maybe seniors, or those who’ve been down that path for a while. Package it for me, Andrew, that control the controllable.

[00:31:43] Andrew Haley: I'll give you a little bit of a story. Back in the early 90s, I just started swimming. I went to a competition in Anagonish, Nova Scotia, and I swam a race. It was 100 meter freestyle. I knew that because I was a disabled athlete that I wanted to beat one athlete. That's all I wanted to do. His name was Timmy. And what happened was I looked at the scoreboard at the end of the race and Timmy beat me. I finished last and I hopped over to where I was sitting and my coach came over and said, how did that go? And I'm like, well, you saw I was last. I lost. And I was defiant. I was dejected. And he goes, well, I don't actually see it that way. And I was getting irritated because I'm like, it was the fact I lost. And he said to me, what was your best time? I said, well, my best time was 1 minute and 20 seconds. He said, what did you go? I said, 1 minute and 18 seconds. He said, you know what you did? I was like, well, what did I do? He said, you just set a personal world record. And there's a difference there in terms of world records. When I see personal world records, essentially is the best time.

He said, but what happened was is that going into this race you were only focused on Timmy. You weren't focused on your starts, you weren't focused on your turn, you weren't focused on your propulsion, you weren't focused on what you could control. You were too worried about what he was going to go. So, I could have gone to best time, but because I didn't beat him, I considered that a failure. He said, you need to start controlling what you can control. I started realizing that I had the power to control my own body ship, let's call it. Not only did I beat Timmy, I beat a lot of other people because I blocked out the things that were going to conspire against me. I just focused on what I knew that I could handle, and I made things happen. So, my advice to the people listening is to really put aside the doubts, really put aside what you cannot control.

I cannot control the fact I lost my leg. I can complain about it. It's not going to help. So, I have to move past that. You can't complain that unfortunately you're a paraplegic, a quadriplegic, lost your arm, lost your leg, something else happened. You can't. You can complain about it, and somebody might listen, but it's not really going to get you too far. So, you have to deal with it and you have to embrace it the best you possibly can. Embrace that situation. I'm reminded a little bit by, I can't remember his name, I think it's Jacob, but I could be wrong. The individual athlete who was part of the Humbolt Broncos, the goaltender who was paralyzed because of the terrific accident many years ago, and now he competes for Canada in para rowing. He just competed in Paris Paralympics. And amazing how the mindset to put the disability aside and make the best of what is a horrible situation. I've done it, Jeff. You've done it. He's done it. Many have done it. That's why you were in the Paralympics. So, if you need support, go to your local area to get the support from family, from friends, from a sport organization.

And things are a lot better, a lot better than my day. And look what I did. You know, we've gone through my results. So good luck to everybody watching and listening because I think there's some positive moments that you want to do. And the other thing I want to leave with is, consider your life a book. It's going to be written regardless of what you do. Because it's going to be written in regards to what you do. If somebody's to read that book in five years and 10 years, would you not want them to read good things about you? I would. That's why I try to do good things with my kids and what I'm doing. So, make sure that you're always going out there with the best foot forward and the best job you can put forward. So that book that is being written by AI or whatever, again, this is all fictional, is being the best version of yourself without excuses, without whining. Maybe a little, but basically being as positive you can be to move yourself forward with the support around you, which I'm sure is just a matter of asking.

[00:36:16] Jeff Tiessen: Yeah, so well said, Andrew. Coming from a Paralympic champion with huge dreams and goals and aspirations and accomplishments, you know, you've kind of boiled the ocean down to small victories and one step at a time and small achievements and appreciating those. Right? And that's important too.

Thank you so much for the time this morning. And if you want to learn more about Andrew, plenty to learn. And you can see some of his clips from his presentations at Andrew Haley.ca. Again, thank you so much.

[00:36:59] Andrew Haley: A lot of fun anytime and good luck everybody.

[00:37:02] Jeff Tiessen: This has been Life and Limb. Thank you all for listening. You can read about others who are thriving with limb loss or limb difference and plenty more at Thrivemag.ca. And you'll find our previous podcast episodes there too. Until next time Live Well.

Hosted by

Jeff Tiessen, PLY

Double-arm amputee and Paralympic gold-medalist Jeff Tiessen is the founder and publisher of thrive magazine. He's an award-winning writer with over 1,000 published features to his credit. Recognized for his work on and off the athletic track, Jeff is an inductee in the Canadian Disability Hall of Fame. Jeff is a respected educator, advocate and highly sought-after public speaker.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?