Phantom Limb Pain Modern-Day Approaches to an Age-Old Problem

Author: Thrive Staff Writer

It’s a new morning. A computer screen begins to glow, illuminating a hopeful expression. The office begins to stir with activity; the first sips of coffee are made.

Near her building, the eternal currents of the Saint John River roll and surge along a wide bend, and Wendy Hill puts down her cup and begins to work.

As an occupational therapist at The Atlantic Clinic for Upper Limb Prosthetics at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at the University of New Brunswick, Hill takes great pride in the pioneering research she and her staff are conducting. She takes great pleasure in the real results of helping people feel better.

“I’ve worked with patients who have endured phantom limb pain for forty years yet manage a bright disposition through it all. Our techniques continue to progress and improve, and when you see someone find relief for the first time, when you make a difference with someone tormented with chronic pain, it is very rewarding,” Hill shares.

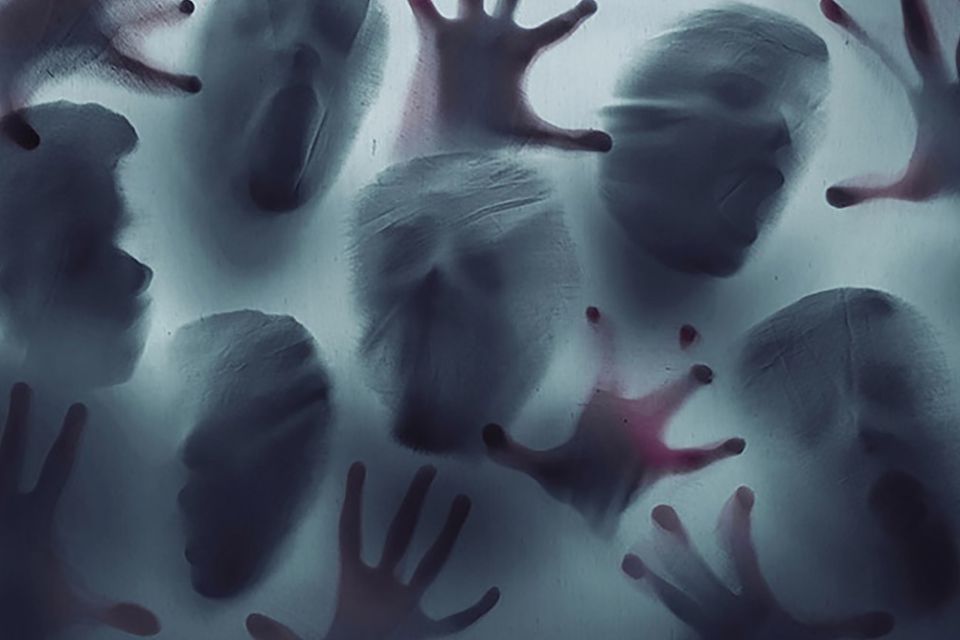

Phantom limb pain (PLP) is an inadequately defined phenomenon, one that most amputees experience, felt as severe pain seemingly located in the missing part of the body. Like other chronic pain conditions, it can leave one incapacitated when it presents itself.

As an occupational therapist at The Atlantic Clinic for Upper Limb Prosthetics at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at the University of New Brunswick, Hill takes great pride in the pioneering research she and her staff are conducting. She takes great pleasure in the real results of helping people feel better.

“I’ve worked with patients who have endured phantom limb pain for forty years yet manage a bright disposition through it all. Our techniques continue to progress and improve, and when you see someone find relief for the first time, when you make a difference with someone tormented with chronic pain, it is very rewarding,” Hill shares.

Phantom limb pain (PLP) is an inadequately defined phenomenon, one that most amputees experience, felt as severe pain seemingly located in the missing part of the body. Like other chronic pain conditions, it can leave one incapacitated when it presents itself.

Phantom limb pain (PLP) is an inadequately defined phenomenon, one that most amputees experience, felt as severe pain seemingly located in the missing part of the body. Like other chronic pain conditions, it can leave one incapacitated when it presents itself.

Presently, scientists are discovering applications of a new technology for PLP reduction, giving hints of an exciting future. At the same time, most doctors are remarkably receptive to traditional medicine and holistic approaches for the issue; diverse tactics for diverse pain. As part of her university research, Hill is working hard, adding to the data, hoping her clinic and the world may soon better understand the phenomena.

The Atlantic Clinic team is performing targeted research as they use virtual reality for phantom pain relief. They treat upper-limb patients only, and their virtual reality set-up is sophisticated, not for its detailed life-like graphics, but for the high-tech sensors and the meticulous collection of data.

“Our protocol is intense,” Hill says. “Patients come twice a week for an hour – 15 sessions. They wear electrodes that measure how they interact with the computer graphic version of mirror therapy. Mirror therapy works well but does not tell us what the muscles are doing. Our study uses an augmented virtual limb, moved about as we measure patient reactions.

We want to know why this is working, which muscles and nerves are reacting and how. The virtual limb on our screen is rather crude-looking, yet it works as the patient’s brain believes it is their limb when they see it move at their whim. At first they might not move it well; it must be learned. Exercises guide them, helping them learn how to keep the muscles quiet.”

During Phantom Motor Execution (PME) treatment, electrodes fastened to the patient’s residual limb receive electrical signals meant for the missing limb, which are then interpreted by AI algorithms and converted into movements of a virtual limb in real time.

Hill is passionate about her mission. “We treat all ages, from children to elderly amputees. Phantom limb pain is felt in many ways. When a patient first arrives, we spend time asking them to define what they are feeling. Some describe it as crushing, some as stabbing, and others as severely shooting flares of pain that are constant. It is not psychological. It is real. It originates in the central nervous system. The part of the brain assigned to the affected limb is dealing with a change as the severed nerves can no longer perform the same task. Sometimes the nerves are overactive, too busy. We must trick the brain into calming this down. We find that even talking about their phantom limb pain helps. We dispel notions that it is psychological, we comfort, we understand. There are a variety of remedies. Some medications quiet this down. Massaging the limb works at times. Using compression can reduce phantom limb pain, and sometimes simply wearing a prosthesis helps.”

Hill’s research is based on the work of Dr. Max Ortiz Catalan of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, who published his theories in the journal Frontiers in Neurology. His emphasis is on allowing the patient to stimulate and reactivate those dormant areas of the brain… neural circuitry that must adapt to new roles after amputation. Catalan believes it is useful to “exercise” the missing limb and many case studies agree.

As research races ahead, brain-to-computer interface technology is beginning to resemble the stuff of science fiction movies. In a Utah lab, a man’s new bionic arm offers feedback, providing sensations so delicate he can hold an egg. He “feels” with it. Portable prototypes of this technology are not that far off. Australian research involving spinal cord injury patients are advancing nerve rerouting, resulting in hands regaining function. Yet, while hearing “Luke Skywalker” as a descriptor of new prosthetic technology may excite many amputees, others are more interested in finding the pain relief they need so urgently by using ancient methods.

“For any treatment of phantom limb pain, none are 100% effective and then done,” says Dr. Amanda Mayo, who specializes in amputee rehabilitation at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. “An expert in phantom limb pain sometimes knows what to suggest,” she says. “Try to find help from a specialist.”

The Atlantic Clinic team is performing targeted research as they use virtual reality for phantom pain relief. They treat upper-limb patients only, and their virtual reality set-up is sophisticated, not for its detailed life-like graphics, but for the high-tech sensors and the meticulous collection of data.

“Our protocol is intense,” Hill says. “Patients come twice a week for an hour – 15 sessions. They wear electrodes that measure how they interact with the computer graphic version of mirror therapy. Mirror therapy works well but does not tell us what the muscles are doing. Our study uses an augmented virtual limb, moved about as we measure patient reactions.

We want to know why this is working, which muscles and nerves are reacting and how. The virtual limb on our screen is rather crude-looking, yet it works as the patient’s brain believes it is their limb when they see it move at their whim. At first they might not move it well; it must be learned. Exercises guide them, helping them learn how to keep the muscles quiet.”

During Phantom Motor Execution (PME) treatment, electrodes fastened to the patient’s residual limb receive electrical signals meant for the missing limb, which are then interpreted by AI algorithms and converted into movements of a virtual limb in real time.

Hill is passionate about her mission. “We treat all ages, from children to elderly amputees. Phantom limb pain is felt in many ways. When a patient first arrives, we spend time asking them to define what they are feeling. Some describe it as crushing, some as stabbing, and others as severely shooting flares of pain that are constant. It is not psychological. It is real. It originates in the central nervous system. The part of the brain assigned to the affected limb is dealing with a change as the severed nerves can no longer perform the same task. Sometimes the nerves are overactive, too busy. We must trick the brain into calming this down. We find that even talking about their phantom limb pain helps. We dispel notions that it is psychological, we comfort, we understand. There are a variety of remedies. Some medications quiet this down. Massaging the limb works at times. Using compression can reduce phantom limb pain, and sometimes simply wearing a prosthesis helps.”

Hill’s research is based on the work of Dr. Max Ortiz Catalan of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, who published his theories in the journal Frontiers in Neurology. His emphasis is on allowing the patient to stimulate and reactivate those dormant areas of the brain… neural circuitry that must adapt to new roles after amputation. Catalan believes it is useful to “exercise” the missing limb and many case studies agree.

As research races ahead, brain-to-computer interface technology is beginning to resemble the stuff of science fiction movies. In a Utah lab, a man’s new bionic arm offers feedback, providing sensations so delicate he can hold an egg. He “feels” with it. Portable prototypes of this technology are not that far off. Australian research involving spinal cord injury patients are advancing nerve rerouting, resulting in hands regaining function. Yet, while hearing “Luke Skywalker” as a descriptor of new prosthetic technology may excite many amputees, others are more interested in finding the pain relief they need so urgently by using ancient methods.

“For any treatment of phantom limb pain, none are 100% effective and then done,” says Dr. Amanda Mayo, who specializes in amputee rehabilitation at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. “An expert in phantom limb pain sometimes knows what to suggest,” she says. “Try to find help from a specialist.”

“For any treatment of phantom limb pain, none are 100% effective and then done,” says Dr. Amanda Mayo, who specializes in amputee rehabilitation at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. “An expert in phantom limb pain sometimes knows what to suggest,” she says.

Awareness of phantom pain studies is important for amputees as new methods are succeeding at early stages of the research with limited side-effects. With pain being so complex and the sensations so unique to each individual, it will still be a while before scientific opinions are set, yet a distressed patient might consider trying many of the new methods without worry of injury.

“Chronic pain affects everything: mood, function, relationships,” says Dr. Mayo. “Patients can get desperate. It’s rare to never have phantom limb pain, but for most it improves over time. Amputees have many options, from medications, surgical techniques such as TMR (Targeted Muscle Reinnervation), cannabis oils, visualization, mental imagery, self-massage, becoming more precise with fitting sockets, and virtual reality therapy. Some patients need to be desensitized to dampen the nerve signal… with heat or cold, or with topical prescriptions, and some improve with acupuncture. Medicine would love to understand why some respond and some do not. We need more evidence.” Sunnybrook is also expanding the use of virtual reality for phantom limb pain. Dr. Mayo adds, “We must retrain the brain that this is where the limb ends.

The brain function is dealing with change. Healthcare is always a risk/benefit equation, and these virtual reality therapies have no adverse effect. Presently we use a Leap Motion device that is smaller than a deck of cards, providing the opportunity to have therapy sessions at home. The program can be used on a laptop or iPad. We also encourage mindfulness apps and deep breathing, making the home an extension of clinical therapy while also maintaining face-to-face visits.”

Practicing therapy at home while alone. Being aware of your own body. Mindfulness, deep breathing and imagery. Sounds like yoga and associated disciplines, practices meant to mend a pain sufferer’s disposition if not the physical injury. All agree this is an important component of the healthy equation, whichever source one chooses to reach inner peace.

Robynn Nierop of Toronto’s Imagine Yoga and Wellness has crafted her firm’s adaptive yoga services around a client base that is splendid in variety… inclusive programs for “unique populations”. Nierop maintains that all can benefit from this kind of training. “It’s not just the poses,” she emphasizes, “but the breathing, of which we use many techniques, and the mindful mindset. Anyone who is unsettled, ungrounded or endures feelings of anxiety will see results from our practices – outcomes over time. Many of us are getting lost in telling ourselves stories,” Nierop observes, “becoming stuck in a negative, pessimistic mindset. Feeling better about where we are and who we are is a matter of choosing to change our belief system away from the pessimistic. It’s a domino effect. It begins with thought.

“I am not downplaying the very real physical sensations amputees have with phantom limb pain,” she asserts. “It is not psychological. But we deepen our trials by what we think. Negative attitudes must change; an honest appraisal of ‘this is where I am’ must be acted upon. By acknowledging where we are at, we create the path to where we want to go.”

This philosophy is universal, not just from yoga instructors. In his best seller The Art of Racing in the Rain, highlighting the aspect of choice we all carry, even Garth Stein’s dog narrator said: “That which we manifest is before us; we are the creators of our own destiny.”

And until science finds all of the answers, we do our best. The river rolls on.

“Chronic pain affects everything: mood, function, relationships,” says Dr. Mayo. “Patients can get desperate. It’s rare to never have phantom limb pain, but for most it improves over time. Amputees have many options, from medications, surgical techniques such as TMR (Targeted Muscle Reinnervation), cannabis oils, visualization, mental imagery, self-massage, becoming more precise with fitting sockets, and virtual reality therapy. Some patients need to be desensitized to dampen the nerve signal… with heat or cold, or with topical prescriptions, and some improve with acupuncture. Medicine would love to understand why some respond and some do not. We need more evidence.” Sunnybrook is also expanding the use of virtual reality for phantom limb pain. Dr. Mayo adds, “We must retrain the brain that this is where the limb ends.

The brain function is dealing with change. Healthcare is always a risk/benefit equation, and these virtual reality therapies have no adverse effect. Presently we use a Leap Motion device that is smaller than a deck of cards, providing the opportunity to have therapy sessions at home. The program can be used on a laptop or iPad. We also encourage mindfulness apps and deep breathing, making the home an extension of clinical therapy while also maintaining face-to-face visits.”

Practicing therapy at home while alone. Being aware of your own body. Mindfulness, deep breathing and imagery. Sounds like yoga and associated disciplines, practices meant to mend a pain sufferer’s disposition if not the physical injury. All agree this is an important component of the healthy equation, whichever source one chooses to reach inner peace.

Robynn Nierop of Toronto’s Imagine Yoga and Wellness has crafted her firm’s adaptive yoga services around a client base that is splendid in variety… inclusive programs for “unique populations”. Nierop maintains that all can benefit from this kind of training. “It’s not just the poses,” she emphasizes, “but the breathing, of which we use many techniques, and the mindful mindset. Anyone who is unsettled, ungrounded or endures feelings of anxiety will see results from our practices – outcomes over time. Many of us are getting lost in telling ourselves stories,” Nierop observes, “becoming stuck in a negative, pessimistic mindset. Feeling better about where we are and who we are is a matter of choosing to change our belief system away from the pessimistic. It’s a domino effect. It begins with thought.

“I am not downplaying the very real physical sensations amputees have with phantom limb pain,” she asserts. “It is not psychological. But we deepen our trials by what we think. Negative attitudes must change; an honest appraisal of ‘this is where I am’ must be acted upon. By acknowledging where we are at, we create the path to where we want to go.”

This philosophy is universal, not just from yoga instructors. In his best seller The Art of Racing in the Rain, highlighting the aspect of choice we all carry, even Garth Stein’s dog narrator said: “That which we manifest is before us; we are the creators of our own destiny.”

And until science finds all of the answers, we do our best. The river rolls on.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?